A Brief Performance History

A Midsummer Night’s Dream is the most produced and performed play in the world. It has been the perennial champion for decades. This is partially because it is by the world’s most popular playwright, William Shakespeare, but it has several other distinct performance characteristics that place it ahead of even more read and studied titles—like the great tragedies—by the same author.

As is true of all of the comedies, it enjoys a slight advantage in the professional theatre over heavier fare from other genres. It is also an ensemble piece with rewarding roles for a large cast that makes it popular in amateur theatres, instead of relying on a central starring (and difficult-to-cast) role, like Hamlet, for example. And unlike the aged characters of King Lear, Macbeth, and most of the history plays, many of the characters of Midsummer are adolescents who can be believably portrayed by students in colleges, universities and secondary schools. (Indeed, only one character in the play—Hermia’s father, Egeus—must logically be characterized as even middle aged.)

It is also possible to cast far more women in substantial parts than is easily possible in most other Shakespeare plays, which also makes it attractive.

As a result, MND is widely produced in professional theatres, in amateur and community theatres, and surges to a huge lead among educational theatres at all levels of the spectrum. There are thousands of productions, world-wide, every year.

Little in the play’s early history gave any indication that it would come to dominate the theatre as it now does. The title page of the first quarto tells us that it had been publicly performed by the theatrical company to which Shakespeare belonged “sundry times,” but there are no certain references to exact times and places dating from Shakespeare’s lifetime, as there are for most of the canon. (It is possible, but far from certain, that “the play of Robin goode-fellow,” which was performed at court in January 1604 and mentioned in a contemporary letter was Shakespeare’s play. We get no other even plausible reference until 1630, when it was performed at Hampton Court.)

We have to piece together the play’s earliest history conjecturally. Most of Shakespeare’s mature plays were clearly conceived for outdoor amphitheatres like the Globe, but despite a history of spectacular productions, Midsummer can be performed on a virtually empty stage. It does not require anything but a large open space with minimal properties for a performance.

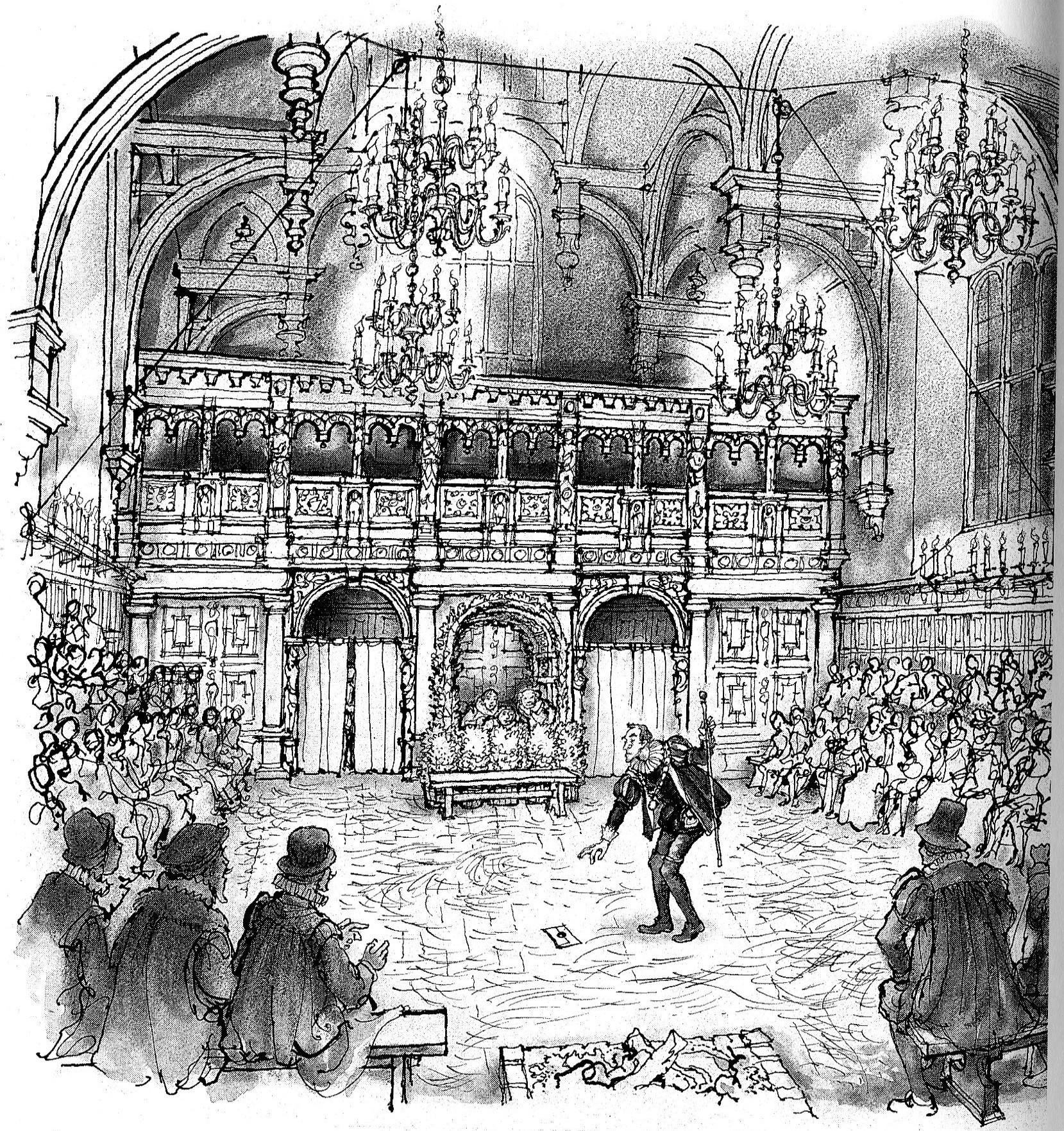

There is a long tradition that the play was commissioned to celebrate an aristocratic wedding. There is no solid evidence for this, but the internal subject matter—so concerned with nuptial entertainments—does make this seem (somewhat) plausible. It could have easily been performed by a touring company in a large hall of an aristocratic home of the period or one of the Inns of Court, such as the one pictured below, or even outdoors as it often is today.

A performance at Middle Temple Hall in London

Used by permission of the Folger Shakespeare Library under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Even without believing in this inferred, rather than evidence-based, proposition it is reasonable to speculate that the play was written with maximum flexibility in mind and not specifically to be performed in one of London's purpose-built theaters.

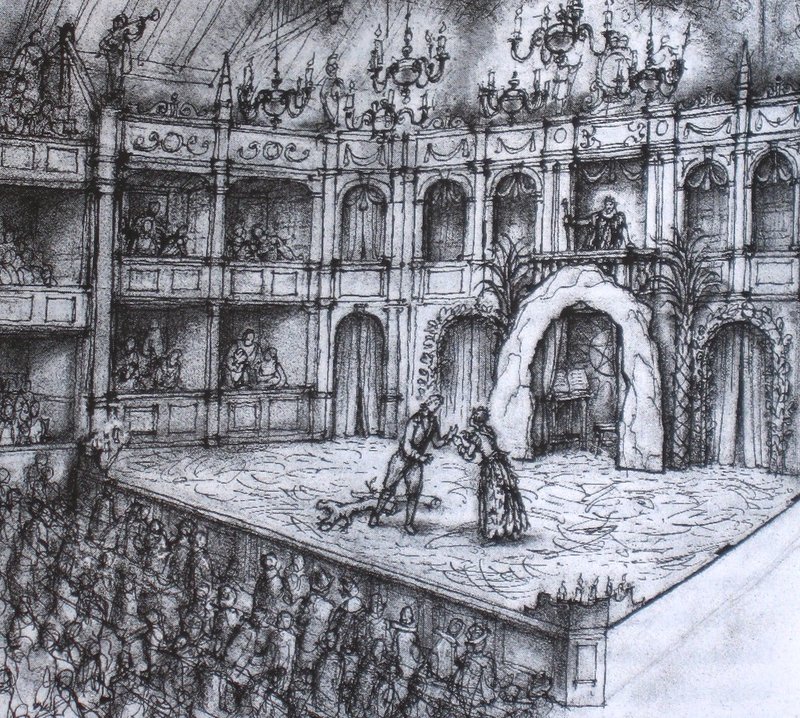

Given its subject drawn from rural folklore, it is easy to see how it might have been imagined originally as material for the humble conditions offered by the central courtyards of inns of provincial towns where temporary stages were erected for touring performances:

Used by permission of the Folger Shakespeare Library under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

A touring performance

The reference on the title page of the first quarto suggests that the play was eventually performed by the Lord Chamberlain’s Men in some London venue, perhaps The Theater or The Curtain, in Shoreditch. It might have moved to the Globe when the company built that playhouse in 1599, but that space made possible far more sophisticated staging than anything Midsummer requires, and the very fact that the play was printed (thus making it available for performance by rival companies) in 1600 suggests that it was not a part of the active repertoire.

A performance at the Globe

Used by permission of the Folger Shakespeare Library under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

At some point later than 1608, when Shakespeare’s company began performing at their indoor playhouse, The Blackfriars’, Midsummer was revived in a production revised for this space and the emerging new performance conventions of this more intimate playhouse. (In addition to the 1630 performance listed above, this information can be inferred from the allotment of plays, including A Midsummer Night's Dream, to Thomas Killigrew in 1669 based specifically on the fact they had been performed at the Blackfriar’s before the Civil War.)

Act divisions with musical interludes—which were necessary for the trimming of candle wicks used for indoor lighting—were added. A stray stage direction ("Tawyer with a Trumpet before them.") appearing in the Folio for the first time, which specifically names a musician not known to have been a member of the company before 1622, suggests that this revival happened well after Shakespeare’s death. The placement of the play inconspicuously among the comedies in the Folio again intimates that Midsummer was not a particular success upon the occasion of this revival.

A reconstruction of the Blackfriars Theatre.

Used by permission of the Folger Shakespeare Library under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

After the Restoration the play was revived in a production about which we know little, but that diarist Samuel Pepys famously condemned as “the most insipid ridiculous play that ever I saw in my life.” Shakespeare’s verbal and imaginatively intense comedy was little suited for the tastes of Restoration audiences, who preferred a more continental style of theatre, and it soon ceased to be performed.

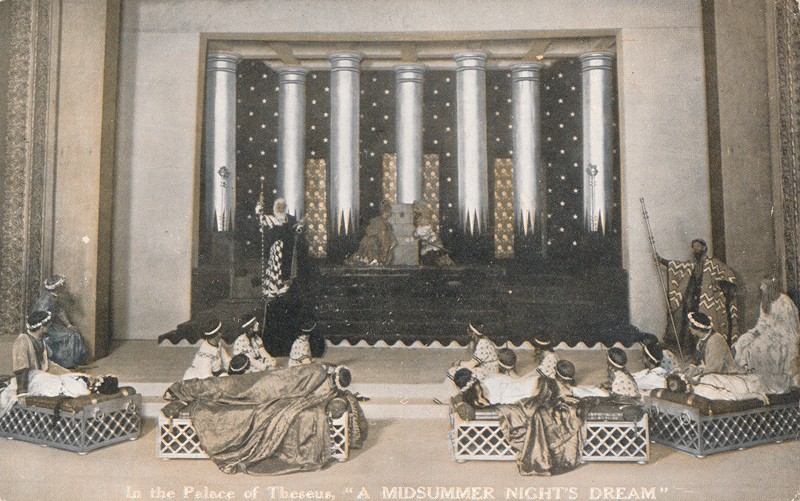

It was replaced by Henry Purcell’s 1692 opera, The Fairy Queen, and later by David Garrick’s 1755 musical (with twenty-eight additional songs) called The Fairies. From then until the 19th Century the title was attached to performances that cut dialogue extensively, as well as whole sub-plots, but then filled out the evening with grand spectacle. Pageants, ballets, children’s choruses and a host of sentimental devices reduced the play to a slight fairy tale almost without plot. It became traditional for Oberon and Puck to be played by women, and the fairies by a corps de ballet. With the advent of illusionistic scenery, the backdrops of Greek temples and other classical vistas often became more important than the foreground action.

Herbert Beerbohm Tree's production of 1900, with dozens of children playing fairies, real grass, and even live rabbits in the forest.

public domain

It was not until Harley Granville-Barker reclaimed the play in an early modern-style performance in 1914 that anything like the original play was performed. (It was during this roughly three-hundred year period that the editorial tradition of treating the plays as literature to be read, rather than performance scripts, solidified. It is worth bearing in mind that this legitimately reflected the fact that during that long period, Shakespeare editions of Midsummer really were not performance scripts. The play was only being staged in variety show adaptations that had, at best, tenuous connections to Shakespeare’s original.)

Harley Granville-Barker's staging of PYRAMUS AND THISBE, which compared with Tree's production (above) is more in keeping with early modern stage practice.

Harley Granville-Barker Cast of “A Midsummer Night’s Dream”, Shakespeare and the Players, Center for Digital Scholarship, Emory University.

Throughout the 20th century, this return to an interest in the original text and original performance conditions continued side-by-side with more traditionally lavish productions like Tyrone Guthrie’s 1937 production at the Old Vic starting Vivien Leigh as Titania, accompanied by two dozen ballerina/fairies. Max Reinhardt’s 1935 film with James Cagney as Bottom and Mickey Rooney as Puck was in this spectacular tradition.

Director Peter Hall staged a ground-breaking version for the Royal Shakespeare Company in 1962 (which he turned into a film in 1969, with Judi Dench as Titania) placing the play firmly in Tutor England with an emphasis on the dark side of the folklore involved.

It was Peter Brook’s 1970 production for the Royal Shakespeare Company that ultimately moved the title to the center of the modern repertoire. Often called the most influential Shakespeare production of the 20th Century, Brook’s staging removed the last vestiges of the sentimental and spectacular approaches to the play that had so long dominated the stage.

This production was not an early modern re-creation, however. It was reflective of the psychedelic, sexually liberated ‘60s. Working with designer Sally Jacobs, the set was reduced to a simple white box. Costumes in Athens were “mod” in muted tones, but the fairies wore shockingly saturated gowns in primary colors. Oberon’s entrance in his blue robe was described by one critic as being so vivid “that you could hear it.” The roles of Theseus and Oberon were played by the same actor, as were those of Hippolyta and Titania. The supernaturals were clearly the dream doubles of the Athenian couple. The production explored the play’s darker themes, especially its aggressive and transgressive sexuality. Brook’s Dream not only had no children in it, it was not a production to which to bring them. It was also a production that set new standards for clear, fresh verse speaking.

An RSC publicity photo of Brook's production.

Photo: Wikimedia, fair use.

Brook’s shadow has loomed large ever since, with modern productions of the play seeking to be experimental, innovative, and respectful of the complexities of the text. Many outstanding productions have following in the wake of Brook’s Dream, including those of Robert Lepage in 1992 for the Royal National Theatre, Adrian Noble for the RSC in 1995, Julie Taymor for Theatre for a New Audience in 2013, Dominic Dromgoole at the new Globe reconstruction on London’s bankside in 2013 and Emma Rice for the same venue in 2016. All of these but the Lepage production were filmed and are widely available for viewing from numerous sources.

Nicholas Hytner's 2019 production for the Bridge Theatre in London (later shown on NT Live) essentially exchanged the roles of Oberon and Tytania by reassigning all but the first few of their lines. He became Bottom's gay paramour because of a magical plot conducted by her with Puck.