Doubling in Midsummer

A Midsummer Night’s Dream is a play that seems designed for extensive doubling by actors – that is, actors playing more than one role in the play. A quick glance at the Act-Scene-Character breakdown (see Appendix 1) reveals clear patterns of character groups that disappear from the play for stretches of time, while another group of characters of almost identical configuration replaces them. These two groups may alternate scenes throughout the play, but never appear onstage together. Identification of these groupings, and how they alternate follows:

1. Athenians/Supernaturals

Theseus, Hippolyta and Philostrate always appear together. They are conspicuously absent during the times their supernatural counterparts – Oberon, Tytania and Puck – hold the stage. Since Peter Brook’s groundbreaking production in 1969, it has become almost traditional for Theseus/Oberon to be played by a single actor, Hippolyta/Tytania to be played by a single actor, and Philostrate/Puck to double. These pairings are both theatrically entertaining and thematically resonant. (A number of strict traditionalists insist that this could not have been Shakespeare’s original intention because Oberon and Tytania exit at the end of Unit 33 while Theseus and Hippolyta begin Unit 34. At least on paper, this seems an unmanageable costume change and reëntrance. A half century of theatrical productions have devised so many possible solutions for this problem, ranging from ingenious quick changes, to insertion of a short musical interlude, to reversing the order of Units 34 and 35, to making the change onstage in a highly theatrical manner, that this objection now seems pedantic and quaint.)

2. Egeus/Mechanical

As the lines are assigned in the quartos, Egeus appears only in the first scene and again briefly in the fourth act, but disappears conveniently from the play before the final act. This means that the actor playing this role is available to double one of the mechanicals, usually Quince.

(In the Folio, Egeus is assigned all of Philostrate’s lines from the final act, but the fact that this makes this small part essentially unable to double any other roles is just one among a number of reasons for being skeptical about the authority of this change of line assignments in the Folio.)

3. Mechanicals/Fairies

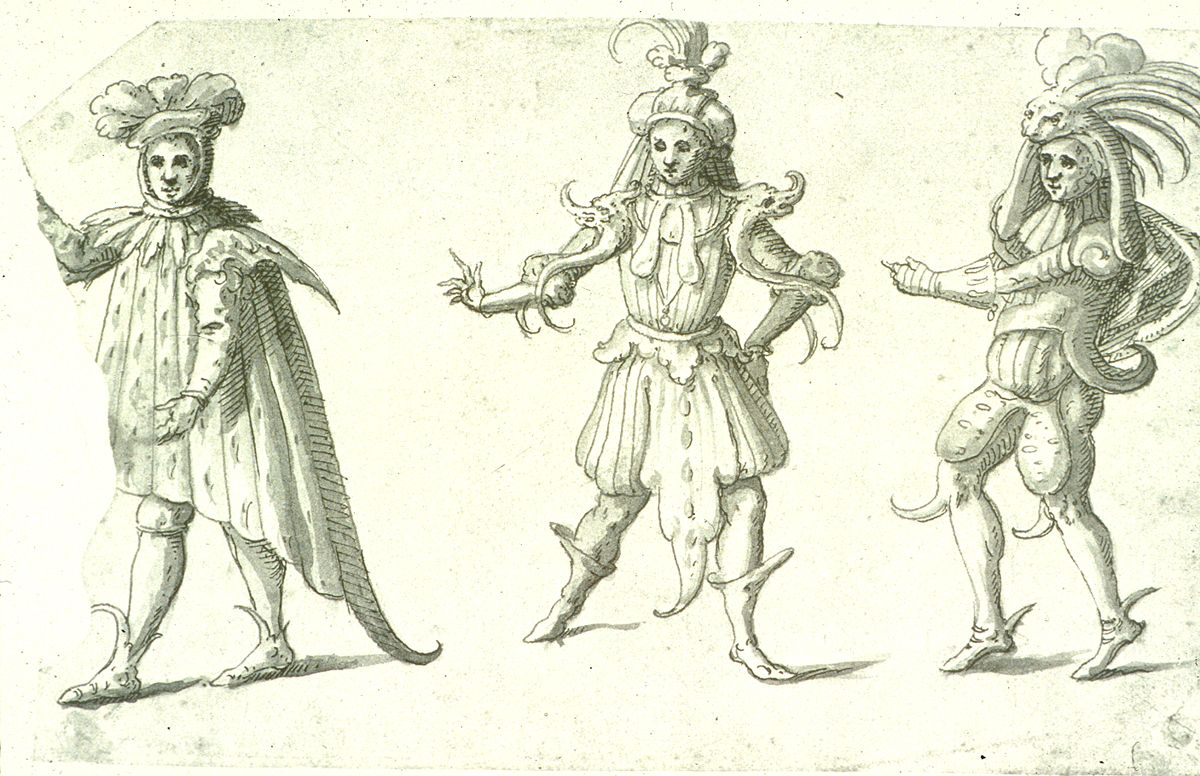

Bottom’s four companions (Flute, Snug, Snout and Starveling) are never on stage with the four named fairies (Peaseblossom, Cobweb, Mustardseed and Moth). The only reason that this is not an obvious doubling is that centuries of anachronistic practice have conditioned a modern audience to think of the fairies as female, and as children. This was not an Elizabethan idea, however. The same masque for which Inigo Jones designed an evocative Oberon costume (which can be seen in the List of Characters, above) also features a set of designs for fairies, which are quite clearly adult men. Although this masque is a separate theatrical work than Midsummer, it still shows that as late as a couple decades after Midsummer premiered “fairies” were still thought of as something like "goblins," not female children. This doubling, too, has now become rather common in twenty-first century productions.

Designs by Inigo Jones for fairies in his masque, Oberon

Note: The play contains characters called “Fairy” in Unit 7, and “First and Second Fairies” in Unit 12, as well as a non-speaking fairy identified as the “Sentinel” in Units 12/13, but there is no reason to think that these are not meant to be played by the same actors that play the named fairies that are already onstage. They are not true doublings, as much as they are simply open assignments. (That is to say, the play does not call for a minimum of eight fairies. Four fairies can do all the jobs.)

Summary:

Without any real issue beyond thinking through the easily-solved transition from Unit 33 to 34, the twenty-five identified characters in the cast list can be played by just 13 speaking actors using the above doublings. (Non-speaking extras are suggested at several points in the play as courtiers to Theseus and as the followers and attendants of Oberon and Tytania, but these are not strictly necessary and the play is more often produced without them that with them in the modern theatre.)

A cast might look like this:

- Theseus/Oberon } played by one actor

- Hippolyta/Tytania } played by one actor

- Philostrate/Puck } played by one actor

- Egeus/Quince } played by one actor

- Hermia } played by one actor

- Lysander } played by one actor

- Demetrius } played by one actor

- Helena } played by one actor

- Bottom } played by one actor

- Flute/Peaseblossom } played by one actor

- Starveling/Cobweb } played by one actor

- Snout/Mustardseed } played by one actor

- Snug/Moth } played by one actor

More Theatrical Choices

In his wonderful book-length discussion of doubling in Shakespeare, scholar Brett Gamboa suggests that if one is willing to be just a bit more theatrically daring, it is possible for both Hermia and Helena to also triple one of the mechanical/fairy pairings. This is possible if the production uses body doubles in the last scene of the play, as they both (conveniently) do not speak after the point that they take their places in the gallery to watch the mechanicals perform Pyramus and Thisbe. This would bring the speaking cast down to 11, although it probably still requires at least two extras.

It is not easily possible to go further than that limit without adopting more overt theatrical conventions (such as actors playing two parts simultaneously) and/or intervening in the text much further, but it is worth noting that it is only because they have interjections in between scenes of Pyramus and Thisbe that Lysander and Demetrius cannot also triple mechanicals. Some modern productions have them do so anyway by reassigning their lines or resorting to more liberties with the traditional staging and text, bringing the speaking cast down to nine.

At its most extreme then, a creative casting might look like this:

- Theseus/Oberon } played by one actor

- Hippolyta/Tytania } played by one actor

- Philostrate/Puck } played by one actor

- Egeus/Quince } played by one actor

- Hermia/Snug/Moth } played by one actor

- Lysander/Starveling/Cobweb } played by one actor

- Demetrius/Snout/Mustardseed } played by one actor

- Helena/Flute/Peaseblossom } played by one actor

- Bottom } played by one actor

Of course, a small ensemble is not always the goal. For amateur and school productions, it is often useful to have a large number of roles available and it is not necessarily desirable to use doublings with less experienced actors. Professional productions, however, usually want to do so. Although it is economically useful to employ a smaller number of speaking actors, the better reason is that the play is theatrically more interesting with virtuosic displays of acting as a result of doubling and tripling. Further the repetition of themes of the play can be highlighted by thoughtful employment of actors in related roles.

Much about the play suggests that this was, in keeping with Elizabethan theatrical custom generally, the original practice. Modern performance history tells us that the play is now more successful and popular when performed in this manner, whether or not it was originally played this way.