Editorial Problems and Principles

The major editorial principles of this edition:

- The editorial aim has shifted from the traditional one that seeks to recover the author’s final “literary” draft (which this editor doubts ever existed in the usually imagined form) to one that seeks to recover his intentions for the work as a performance script.

- The edition was constructed from the collation of early printings, rather than emended from a copy-text.

- In a related—but separate—matter, the editor explicitly rejects the long-standing identification of Q1 as having been set directly from Shakespeare’s holograph “foul papers.”

- Treating the work as a performance script means it is held to be primarily an oral text meant to be spoken and performed. The written form is understood to be a means to an end, not the end in itself.

- The edition is a modern spelling rendition, using American spellings.

- Punctuation is modernized.

- The script is generally divided into the traditional act and scene divisions established in the eighteenth century, but the primary division—which is unique to this edition—is into French scenes for rehearsal purposes.

- Stage directions are extensive (and every attempt has been made to make them complete) but only rarely in the wording printed in early modern editions, which is of uncertain provenance.

- Speech headings are regularized.

- The edition allows for the possibility that some sections of dialogue were intentionally left open-ended in terms of speech assignments.

- All lineation, especially when there are metrical implications, has been reëvaluated.

More complete explanations of these points appear below:

Editorial Aim: A Working Script, Not A Reading Text

This experimental text is an attempt to create, not just a new edition, but a new kind of edition of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. It is also, like all acts of textual and/or literary criticism, an attempt to understand the work of art better, and to help others understand it better. Those things, however, don’t mean that all editions have the same goals, or even the same audiences.

This edition attempts to understand the text as a performance script, rather than a literary text, as has been the de facto case for all other editions since at least the eighteenth century, and arguably from the earliest quarto printings. Some recent editions of MND have been more open to the possibility that the text might serve as a memento of a performance or contain some kind of—at least partial—performance record. Although moving closer to the aims of this edition, these approaches are not the same as looking at the text as (to use an imprecise but useful metaphor) a blueprint for a future performance.

By contrast to existing editions which aim to recover Shakespeare's literary manuscript, the explicit aim of this edition is the historical recovery of A Midsummer Night’s Dream as a script, primarily to serve as the basis for new theatrical productions, along with related creative activities, like classroom performance approaches.

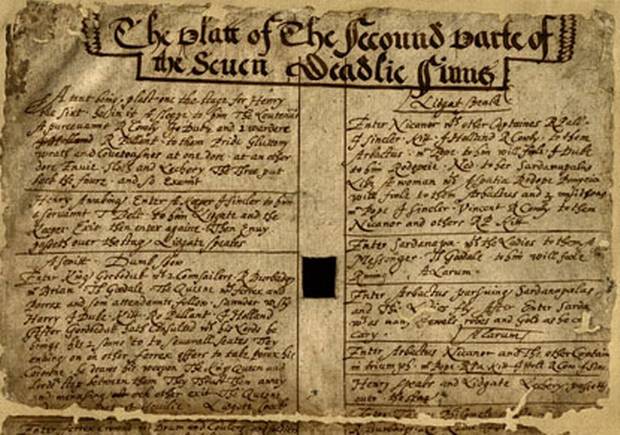

Although there is no serious opposition to the idea that Shakespeare’s play was initially created as a script, there is no extant manuscript evidence to that effect for A Midsummer Night’s Dream, or—for that matter)—any Shakespeare play. The original form of that script must be inferred from extant historical evidence of non-Shakespeare plays (such as rough drafts, scribal copies, backstage “platts” to guide performance, actors' parts in the form of cue scripts, approved books to license production, and working promptbooks) which has been vastly undervalued; and from clues in the early print copies, which likely have been misinterpreted by editors with little or no theatrical experience.

A backstage "platt," or plot, used to indicte the running order of the show.

Wanting to recover the performance script, however complicated by missing evidence that might be, should not be controversial in that no one denies that there once was such a performance script with a material manifestation.

Such an edition has been heavily theorized, especially by the late Barbara Hodgdon, M.J. Kindnie, and others, but no critical edition has undertaken this task.* All editions, in a tradition that dates to the First Folio in 1623, explicitly refer to their audiences as “readers.” This is not just convention. Both the text and apparatus of previous critical editions are designed for literary study (even those versions that have been called “performance editions”) rather than as a basis for new production.†

This is not to suggest that there is anything illegitimate with the aim of these existing literary editions. This edition, in fact, builds on this long tradition in some significant ways. It is to say, however, that it is regrettable that, at present, all critical editions are designed to serve readers rather than practitioners. This is probably what David Scott Kastan was getting at when he wrote that "There are good reasons… for many kinds of editions, though probably not very good reasons for as many of the same kinds of editions as indeed we have… Shakespeare should be available in editions that take the theatrical auspices of the play seriously, recognizing that primary among Shakespeare’s intentions was the desire to write something that could be successfully played.” (p. 123)

Of course, there are many reasons that all critical editions of Shakespeare have been readerly but in the particular case of MND a prominent one is a wide-spread assumption that the literary copy was the same as the theatrical copy.‡ Historically speaking, this is beyond unlikely, so it is to this matter, after a brief detour, that we must next turn.

The Question of Copy-Text

In a departure from what has become standard editorial procedure in the last seventy years this new critical edition of A Midsummer Night’s Dream was edited without a designated copy-text. Instead, for reasons to be elaborated below, it follows the counterproposals of G. Thomas Tanselle, made in his essay, “Editing without a Copy-Text.” §

This edition, therefore—in yet another way it is unlike those currently in print—is, as Tanselle suggests it should be, “a constructed text and not an emended one.” (Millennium, p. 71)**

A Midsummer Night’s Dream may seem a perverse choice for abandoning copy-text editing. It is, after all, a play where the copy-text of choice (Q1) has been nearly unanimously adapted since Edward Capell’s edition of 1768, even by the often contrarian Wells and Taylor Oxford Shakespeare (1986). While over the last fifty years, controversy has engulfed theoretical discussions about exactly what aims editors should—and are even able to—serve, A Midsummer Night’s Dream has for the most part escaped any involvement in the practical implications of this discussion. This is because there is a clear genetic line among the early witnesses with Q1 at its head, followed by a derivative Q2 with no independent authority, and then the Folio text which is set from an annotated copy of Q2 incorporating minor changes apparently from a theatrical manuscript. It has not been considered a difficult play.

Mostly, however, it is the conviction that that Q1 was set directly from authorial papers that most insulated it from intense editorial introspection. The various aims of editors (and even uneditors) essentially converge if the copy-text is a reasonably accurate transmission of the author’s final manuscript, particularly if the Folio can then be interpreted as affirming that only limited changes were later made in the playhouse. But what a wealth of unlikely assumptions are buried in those beliefs.††

Now, twenty-first century scholarship has upset the consensus around both the editorial ability to discern the nature of printer’s copy which lies behind this genetic line and “the rationale of the copy-text.” These uncertainties substantially change the editorial assumptions at play and suggest the need for reëxamining the work from a broader perspective.

The Nature of the Printer’s Copy

The most substantial belief needing reëxamination is the nearly universal hypothesis that the printer’s copy underlying Q1 was Shakespeare’s holograph (foul papers) manuscript. The recent New Oxford Shakespeare (2016), in a typical example, phrases the belief like this: “It has been widely agreed that 1BRADOCK [i.e. Q1] was set from the author's papers. Nothing points to a specifically theatrical manuscript; there are no actors' names, no duplicated stage directions.” (p. 863)

What this wording makes clear is the assumption, relying on a bifurcated categorization system established by W.W. Greg, that if the printer’s copy was not what we would now call a "promptbook," then the only alternative was that it must be authorial papers. Almost from publication of Greg’s theory in his Dramatic Documents from the Elizabethan Playhouses in 1931, prominent peers, especially R. B. McKerrow—who imagined, at minimum, eighteen possibilities for kinds of printer’s copy where Greg saw only two—raised concerns that Greg had created a false dichotomy. Even Greg, himself, noted that his categorization scheme was “perhaps a rash venture.” (p. 191)

But Greg’s “rash” conception became widely accepted, based on the weight of his reputation rather than the evidence he presented, and it heavily influenced editorial assumptions well into the current century. Paul Werstein, building on work by William B. Long, has now thoroughly discredited Greg’s classification system by demonstrating there was never any valid evidentiary basis behind it, but the full implications of this are only beginning to be understood (Early Modern Theatrical Manuscripts).

Theatrical and Literary Manuscripts

The New Oxford Shakespeare’s wording reveals another curious assumption. It is not at all clear why its editors, along with almost all other modern editors, suppose—following Greg—that the basic form of Shakespeare’s rough draft would have been a literary manuscript, rather than a performance script for his company. Tiffany Stern’s Documents of Performance in Early Modern England demonstrates what also seems intuitively obvious, that the standard format for plays in this period was as scripts; and probably not even “finished” and artistically unified ones in any modern sense, but assemblages of prologues, epilogues, scenes, and songs, plus prop letters and pronouncements that were literally read on stage. Far from the finely polished product we now imagine, these scripts retained considerable flexibility about how they were introduced, concluded, and even what events and speeches any given performance might include and to whom they might be assigned.

While the lack of evidence of a bookholder’s (i.e. prompter's) annotation, such as duplicate stage directions or insertion of actors’ names, noted by the NOS editors might suggest that the printer’s copy was not what is now called a promptbook (although Werstine has shown that the surviving evidence of theatrical manuscripts does not support even this conclusion) there is no historic reason for imagining that Shakespeare’s draft was therefore not a theatrical manuscript. Not even Lucas Erne, whose Shakespeare as a Literary Dramatist has vigorously reässerted the literary intentions of the author, suggests that the plays were first drafted in the form in which they would ultimately be printed then later back-engineered into playing scripts.‡‡

Sonia Massai has compellingly reasoned that early modern plays were extensively (although anonymously) edited for print, which has not been readily apparent only because they were “informed by radically different views about what constituted an ‘authoritative’ text.” (p. 2) Andrew Murphy, in a way that implies he is simply stating the obvious, makes a similar, though understated, assertion that “Every text that came to print in quarto needed some element of preparation before it reached publication…” (p. 93)

The most definitive statement of the now questionable view that Q1 represents an almost pure authorial draft is found in the 1994 Oxford Shakespeare individual edition of the play, edited by Peter Holland. Referring to the printer, he flatly states that “Bradock’s compositor(s) worked with a manuscript in Shakespeare’s hand, effectively his rough draft, while fair copy made from the draft stayed with the Lord Chamberlain’s Men.” (Introduction, p. 113). The long shadow of Greg’s false dichotomy is clearly visible, in that Holland again imagines only two possible manuscripts, a rough draft that served as printer’s copy and a theatrical copy that became the company promptbook. This, however, is only a link in a long chain of editors, from John Dover Wilson, Harold Brooks, and R.A. Foakes, to Stanley Wells, Gary Taylor and Terri Bourus who have cited essentially the same evidence but progressively changed their degree of certainty from speculation into possibility, then probability and, with Holland, into statement of fact.§§

Holland’s argument (which he says is just a simple summary of extensive previous discussion) relies on the identification of “incomplete and inconsistent” stage directions that he believes (following Greg) “the bookholder, or prompter, at the theatre would have needed to be more exact.” (Introduction, p. 114) But this is the very evidence about which Werstine has shown Greg was simply wrong. Surviving theatrical manuscripts are messy and contain many of the characteristics of Shakespeare's printed plays. In fact, MND is the play Werstine uses to demonstrate his point (p.130-3).

Holland’s summary of secondary support for the definitive identification of authorial copy rests on a number of putatively distinct Shakespeare spellings in Q1, an argument that has always seemed, at best, inconclusive once subjected to rigorous statistical analysis, but also has been recently fatally undercut by James Purkis on logical grounds (Chap. 5).*** As Purkis has observed, “If Shakespeare’s plays were transcribed before they reached print, unraveling the Shakespearean from the non-Shakespearean, or the preferred spelling of one agent from another, promises to be a barren task. Moreover, it is not necessary to assume that Shakespeare’s plays were transcribed fully before printing to pause over attributing an ‘abnormal’ printed spelling to Shakespeare.” (p. 219)

The conclusion that spelling evidence can be used to definitively identify holograph copy has never been sound, however, unless Shakespeare’s distinctive spellings were just idiosyncratic enough to influence compositors setting the play from holograph papers, but not odd enough to survive intermediate stages of transmission, like scribal copies and theatrical promptbooks.†††

In summary, the wide-spread certainty in the editorial tradition that the text of A Midsummer Night’s Dream has come to us almost unmediated from Shakespeare’s holograph draft is left not only unsupported, but unsupportable. There is, in fact, little reason to believe the quarto (nor, for that matter, the folio) text of the play represents even “a close approach to the author’s manuscript,” as McKerrow warned us nearly a century ago (p. 7).

And there are a lot of historical reasons to suspect that it does not. Compared to the extant manuscript evidence, like scribal copies of Middleton’s Game of Chess vs. Heywood’s holograph theatrical copy of The Captives, it certainly looks a lot more like it was made from a copy prepared for a patron/reader than from a manuscript that saw practical use in the theatre. This unmooring from the dubious authority of the copy-text of choice, and the generally untheatrical assumptions hidden behind it, support Tanselle’s procedure of constructing a new critical edition from the ground up, not least because it allows a fresh look at a significant number of issues of interest to both scholars and practitioners.‡‡‡

(ASIDE) Putting the Principles into Practice: A Specific Example

It is easy to get caught up in the minutia of theoretical quibbles, but these two overarching principles (no designated copy text combined with the aim of recovering the work as a theatrical script) make very real differences to this edition. As an example, take Unit 39, lines 46-62:

- “The battle with the Centaurs, to be sung

- By an Athenian eunuch to the harp.”

- We’ll none of that. That have I told my love

- In glory of my kinsman Hercules.

- “The riot of the tipsy Bacchanals,

- Tearing the Thracian singer in their rage.”

- That is an old device, and it was play'd

- When I from Thebes came last a conqueror.

- “The thrice-three Muses mourning for the death

- Of learning, late deceas'd in beggary.”

- That is some satire, keen and critical,

- Not sorting with a nuptial ceremony.

- “A tedious brief scene of young Pyramus

- And his love Thisbe, very tragical mirth.”

- Merry and tragical? Tedious and brief?

- That is hot ice and wondrous strange snow!

- How shall we find the concord of this discord?

These lines consist of a series of titles being read off a scroll that has been presented to Theseus by the Master of the Revels, and his evaluations of the suitability of each as wedding entertainments.

The bibliographic record from Q1 and F1 is clear, and uncontroversial. In Q1—the nearly universal choice for the copy-text—the entire selection is assigned to Theseus. He reads the titles aloud, and then comments on each one in turn. F1 prints exactly the same words but distributes all the lines that contain titles to Lysander, leaving only the commentary on them to Theseus. Since Q1 is perfectly clear, and is not obviously in error, according to the standard application of the “rationale of the copy-text” this is the solution the editor must mechanically accept to avoid falling into the trap of eclectic editing, or mere subjectivity.§§§ Indeed, several prominent editors (Foakes, Holland, Chaudhuri) explicitly state in their annotations that the alternative found in F1 is more theatrically effective, and probably authorial, but nonetheless reject it in adherence to copy-text editing practices since it was not (in their opinion) the original form.

A 14" tall Folio, next to a Quarto, an Octavo and 2 rare smaller sizes.

A small number of editors accept F1’s redistribution of the lines, reasoning they result from a theatrical revision that Shakespeare made or approved, which de facto makes F1 their copy-text. Whether one treats the section as monologue or dialogue, however, is still dependent on a theory of textual transmission underlying the choice of copy-text that holds the authorial papers come in a literary form and that theatrical choices are the product of later revision.

Both editing without a copy-text and rejecting the identification of the copy for Q1 as authorial holograph challenge that theory. Freed from the “tyranny of the copy-text,” in two senses, the focus of editorial judgement shifts from authority to purpose.

Thinking about what the work is trying to accomplish (as opposed to what text carries the most authority) can clarify that the long-standing binary options are not the only two alternatives. Imagining Shakespeare’s draft as a script opens another possibility: both witnesses might be attempts to reflect an important flexibility of the underlying work that is hard to capture in print and might even be pointless in a literary edition.

The first sixteen lines might have been composed as a unit, earlier than the part of the scene that it now follows, without definitive decisions about how it would eventually be allocated to speakers. This is, in fact, a perfectly common way for both historic and contemporary playwrights—who do not sit down and write their plays straight through from beginning to end—to work. Once fitted into the scene, it might have been clear that the unit was going to function as dialogue, but there would still be no need to specify exactly who feeds the titles to Theseus for his commentary, as it makes little difference who reads them to him. (Nothing about them makes them character specific: they are not even the “thoughts” of a character but just items from a list prepared by someone else.)

In Elizabethan practice, this open-endedness could be maintained even after the cue scripts were prepared, since the crucial lines can be literally read off a prop scroll. A decision could wait until after the show was cast, the circumstances of production known, and the rehearsal process begun. While such ambiguity serves no useful literary purpose, from a theatrical point of view such flexibility is a feature, not a bug.

As to a theory of textual transmission that would explain the witnesses, I propose that Q1 was set from a manuscript with these sixteen lines on a discrete page or slip that had no speech headings at all.**** (This might have been in Shakespeare’s hand, but it is impossible to say since it would look no different if it was a transcription.) Even vague familiarity with the plot—or just mythology—would be enough for the Q1 compositor to surmise that Theseus is the speaker of the commentaries and to provide the speech heading, but in the absence of any stage direction it would not be enough to make clear that the titles could or should be read by someone else. The compositor could easily overlook that the unit is dialogue. If this is the case then, although not obvious on its surface, Q1 is in error.

It is uncontroversial that F1 records a specific theatrical staging by Shakespeare’s company at some point in which Lysander read the titles to Theseus. I do not believe that it records a revision from monologue into dialogue, however. In my judgment the selection was always intended as an exchange with one or more of the lovers, but having conceptualized it that far, the script was as “finished” as the author needed, and perhaps wanted, it to be.

If the essential quality of the exchange is its playful nature and the building of anticipation surrounding the selection of Pyramus and Thisbe, then being more specific might even work against the intended effect. The open-ended state of the text might well be intentional, in order to foster an element of spontaneity in performance.

If this is true, what does it authorize? Possible theatrical solutions are that the Master of the Revels hands the scroll to Lysander, or for that matter, to any one of the lovers, to read the first title. That actor might read all four titles, or s/he could pass the scroll on to a different actor to read the second title, who might similarly keep or pass it. Given that there are four titles proposed and four lovers, it does not require a great leap of imagination to envision the possibility that each of them reads one. All of these options are controlled by the simple passing of a scroll, so it would not have to be worked out in advance and would not need to be the same in every performance.

In fact, redistributing lines is rather standard theatrical practice for this section of the play. All of these arrangements of lines have been used effectively in numerous stagings. But the thesis here is not that these possibilities can work, it is that this is how the script (as opposed to a literary text for readers) is supposed to work. It is a textual argument that the original, authorial form of the play is as a working model that invites and even requires theatrical collaboration, and that the more determined, specified texts are later literary adaptations for readers. The editorial tradition has the direction of revision backwards.

The Extended Implications

This lengthy discussion of just a few lines of text would be unjustified if it did not have larger implications, as the actual effect on the text of the edition is confined to one stage direction and one brief note. Thinking theatrically has ripples throughout the edition, however. To give just a few quick examples:

- Throughout the performance of Pyramus and Thisbe, the onstage audience makes a series of snarky comments about the performance, which are oddly distributed among the speakers. Theseus seems to veer wildly from support to utter disdain for the performance, while Hermia and Helena do not speak at all. Given the example of the manuscript of Sir Thomas More, where it is clear that similar interjections were written without being specifically assigned to speaker until later, it is worth questioning when, why and how the speakers were assigned to these lines.

- Two songs in the play distribute the lyrics differently in Q1 and F1, implying that they were conceived as being flexible. Rather than decide between these alternatives, perhaps a more faithful rendering of the text would leave them unassigned.

- Bottom sings snatches of a popular tune in the wood that was certainly not specifically composed for the play and could as easily have been Will Kemp’s choice as Will Shakespeare’s. Is the best rendering of the script one which preserves one specific comic bit, or one that preserves the comedian’s prerogative?

Oral Works and Written Texts

All of the above points and discussion point to a consideration that should now be made explicit. It is important to establish the relationship of texts to the underlying work.

The work of art is the performed (that is, spoken and acted) play. It is meant to be communicated orally/aurally in the live theater. It is frustratingly complicated to say, conceptually, what any given printed text is in relation to that.†††† We can easily start, however, by saying text and work are not identical in the same way that we might say a musical score is not a symphony, or a screenplay is not a movie.

Although the cases of musical works and films seem clearer cut to most of us than plays, because they do not simultaneously enjoy separate status as works of literature, they are closely related. Printed texts of plays are, like them, incomplete, as opposed to texts of poems or novels. They are an attempt to encode and transmit a framework for the play in writing, not to replace it.

Although it is not a precise designation (because plays also contain embodied performances, designed sets and costumes, etc.) for the purposes of editing a performance script it is useful to approach the work as an oral text. The words and lines to be spoken are fundamentally different, and require different treatment, than many other formal elements of a written play.

(As a though experiment, imagine that we had access to a videotape of one of the Lord Chamberlain’s Men’s performances, which we are asked to transcribe. The spoken words we could recover directly with little disagreement, but things like stage directions and speech headings, as opposed to stage action and speech assignments, have no material presence in performance. They have to be inferred, and might vary widely—especially in form—from one transcriber to the next.)

Stage Directions

Stage directions are among the most problematic parts of Shakespearean plays. Having no manuscripts from the author we are not sure what Shakespeare wrote when drafting his plays, but he seems to have thought them out only loosely and may not have included anything but the barest indications of actions.

Ironically, those few directions about which editors generally agree are authorial are supported with the argument that they are wrong or misleading—placing entrances incorrectly, for example. One such case is Q1's entrance for Helena at the same time that Hermia, Lysander and Demetrius first enter, although she plays no part in the ensuing scene. The logic is that only the author still in the throes of composition would have created mistaken directions.

Although occasionally illuminating about the creative process if this was a conclusive argument, and it is not, preserving errors—even authorial ones—in no way assists production so this edition does not do so.

Bookholders (the term for stage managers in the period), printers and later editors have all created layers of emendation to stage directions, some of which have become traditional. These have more accuracy but no authority.

In keeping with the general principle that this edition should be a practical realization of Shakespeare's intent for the stage (as opposed to being bibliographic scholarship of its printed history) all stage directions have been rethought from scratch. Although quarto or folio directions are sometimes used, stage directions should be considered editorial.

Although this is a departure from standard editorial practice, it is not nearly as radical as it may seem. As far back as the eighteenth-century, editors have expressed concern about the ability to assess the provenance of the stage directions we have. The recent tendency to treat those paratextual elements of the early quartos and folios with the same degree of deference as the textual elements, in case they might preserve something authorial, is unwarranted. It is their function, and not their form, that is their essence.

Speech Headings

Speech headings throughout the play have been silently regularized. There are some interesting variations in the early printed editions, such as “Tyt.” and “Quee.” or “Queene” to designate Tytania, but the idea that these are psychologically telling about authorial intent—a theory very popular in the late twentieth century—now seems unlikely. Printing studies show that type shortages, especially of lower case ys and upper case Qs forced compositorial choices about speech headings. As the case for Q1 being set from holograph papers has fallen apart, it also seems less likely that the variations are authorial. Maintaining confusing variations in speech headings appears pointless outside of documentary editions. Again, it is their function, and not their form, that is their essence.

Spelling and Orthography

This is a modern spelling rendition, using standard American spelling. A number of orthographical considerations come into play, however, about how to render rhythmically and metrically important elements of the text on paper. These have led to some departures from a typical stylesheet. Even in “Reader Mode” distinctions between sounded (ed) and unsounded (‘d) past tense verb endings are preserved. Although once very common, this practice has generally fallen out of favor. (Modern editions have tended to ignore eighteenth and nineteenth century orthography precedent and opt for ease of reading.) It is helpful to reassert precedent for the purposes of this edition, however.

Performer mode directly confronts the problem of how best to represent an oral text in print. In “Performer Mode” every effort is made to indicate orthographically all elisions and contractions with apostrophes. Sounded past tense verb endings get an additional accent mark (èd), as do any unusual accentuations. Expanded endings and glide vowels are marked with a dieresis, as in (ïon) endings, words like (confërence) when the meter calls for added syllables, and a couple of archaic possessives (moonës, nightës). The greatest departure is to repurpose this symbol, a superscript gamma, (ᵞ) in places where words—especially names—are combining syllables that are sometime separated in modern usage, like (Hermᵞa) and (Thesᵞus). While it is common to treat Hermia and Theseus as three-syllable names, they are usually—although not always—treated as two in this play.

Two other kinds of orthographic rendering have been added, inspired by Edward Capell's innovative edition of 1768, which sought to include at least some indications of stage business symbolically. Changes of address with speeches are marked with a double m-dash (——). Text in bold italic indicates a thing or person "pointed to" or indicated. Capell also included a category for props delivered, but these are incorporated into the stage directions in this edition.

The directly performable words of the play are rendered in serif type, like this:

- "Shakespeare's words, to be spoken onstage, are in this typeface."

All other aspects of the play, like stage directions, speech headings, and section headers, appear in this san serif font.

Punctuation

Punctuation has been modernized in this edition, also.

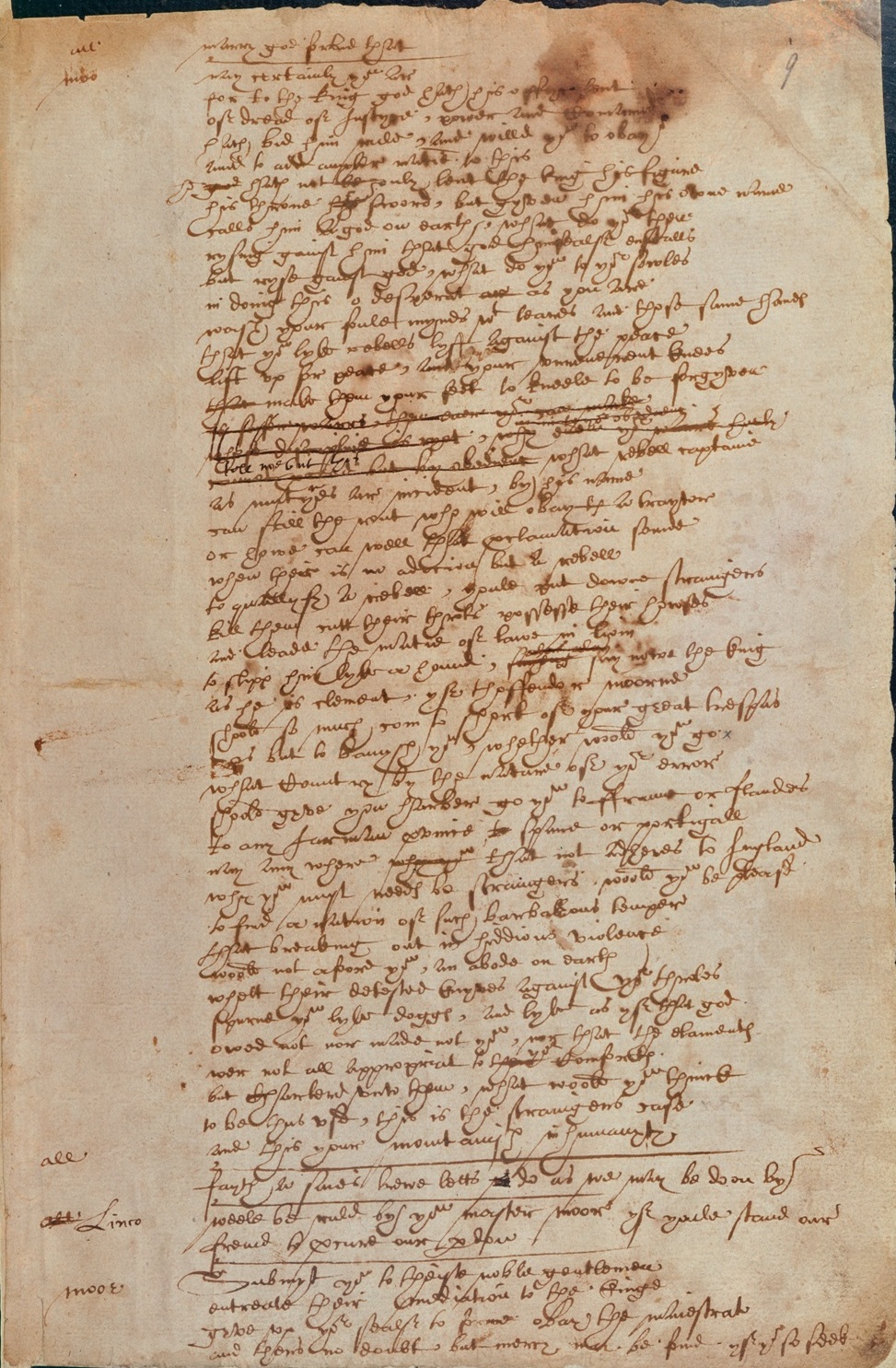

Punctuation in all early modern texts, was inserted by the printing house and not by the author. (Indeed, the one fragment of a play that some scholars argue is in Shakespeare's handwriting—the "Hand D" section of Sir Thomas More—has virtually no punctuation at all.) Grammatical rules for consistent practice did not yet exist, so it is relatively arbitrary.

A brief addition to Sir Thomas More controversially argued to be in Shakespeare's hand.

The usefulness of consulting the quarto and folio editions of the play is that their punctuation tends toward the rhetorical and is far less fussy than is modern practice.

Although this edition has silently modernized punctuation throughout, it has done so with a bias toward preserving the longer rhetorical phrases, which are so useful to actors, over shorter phrases which are intended to illuminate the grammatical structure. The semicolon is not the actor's friend. No hesitation has been felt about bending modern rules if the resulting choices assist actors to see and feel the performance arc of a speech.

Structural Divisions

A Midsummer Night’s Dream has an easily discernable three-part organic structure: what happens before the woods, what happens in the woods, and what happens after the woods. Traditional act and scene distinctions beyond that are simply navigational conveniences to assist with identifying specific moments in the work or specific places in the text, and not properties of the work itself.

For convenience, almost all printed editions of the text incorporate the act designations from F1, which were added long after the play was first performed, possibly marking pauses used during a revival in a candle-lit indoor venue. While these might have been necessary to trim candle wicks at some point, these performance breaks are no longer needed, or used, in the modern theater. (In modern performance, the play is commonly performed in two parts with an intermission—a.k.a. interval—usually taken in the middle of Act III.)

Most print editions also follow a further division into scenes first used in ROWE, which (in the case of MND, not always perfectly) happen whenever there is a full clearing of the stage by all actors.

So long as these divisions are recognized as artificial navigation aids and place markers, they are useful. Throughout this edition these traditional markers are referenced for these purposes, and for cross-referencing with other editions. They should not, however, be conceptualized as either literary or theatrical structures.

This edition is further divided into “French scenes,” because they are the practical building blocks of the action, and also the fundamental divisions used in theatrical rehearsals. To distinguish them from the traditional “English scenes” that Rowe used, these are labelled Units. These should be quite useful for anyone using this edition practically, but (since literary editions are not intended for practical use) are not common in other print editions.

Lines and Conventions

Verse is recognizable because it is printed in lines that do not run to the right margin, and which begin with a capital letter. Prose is printed in a wide column with text that runs to the right margin and is most easily recognizable because new lines of text do not begin with capital letters.

Split lines, i.e. single lines of verse shared between two or more speakers, are printed with the second speaker's words indented beyond the end of the first's.

The early texts have some issues with verse lines printed as prose, and vice versa, which have been silently corrected in this edition. Most importantly, around thirty lines in the play are discernably regular iambic pentameter but were not so set in one or more early editions. These are found mostly in Units 38 and 39.

In the fairy’s speech that opens Unit 7, traditional relineation (dating from Pope) has been rejected because it implies the lines are written in anapestic dimeter, but as explained in the accompanying note, this editor scans the lines in iambic tetrameter.

Annotation and Commentary

This edition is much more heavily annotated and contains far more commentary than comparable modern literary editions, possibly because this is a digital edition where word counts are not financial considerations. (One of the major purposes for creating different user modes, however, is to separate the kinds of notes by purpose to avoid information and interface overload.) Some of it, like glossing in “Reader Mode” and mythology notes in “Student Mode” should seem familiar.

In numerous other cases, distinct differences of approach will be seen. Textual notes in literary editions, for example, tend to record emendation of the copy text. Such notes are tremendously useful, but a serious flaw with most copy-text editing is that it hides the degree to which an editor decided not to emend although a textual issue exists. Once again bibliography trumped performance.

It was once quite common, for example, for editors to concern themselves with metrical irregularity of lines—assuming that such irregularity probably indicated transmission errors. Mid- to late-twentieth century editors became far more reluctant to emend even when they considered such errors likely, unless they were certain what Shakespeare wrote. But as they began leaving more and more ambiguous cases unaltered, they also stopped annotating any instances where meaning was not hindered. Perhaps this is fine for readers, but generations of performers have been left repeatedly scanning syllables and doubting their own judgment when even blatant problems are ignored. Rehearsal halls are stacked with dozens of editions because it is often necessary to consult many, many critical editions to find confirmation that a crux exists. This edition annotates such metrical irregularity, and often offers more than one performance possibility in the notes. Notes are intentionally repetitive when the same principal applies as when, for example, the same shortening of a name recurs. It is not necessary to consult the notes for every instance once you have learned the principle.

This edition also tries to note instances where performable textual alternatives exist in early editions or in the long history of emendation. (By contrast, minor—and uncontroversial—bibliographic issues, like typographical errors, are silently corrected.) Even when a clear choice has been made for the purposes of this edition, it is still useful to the performer to know of viable alternatives.

Particularly in “Performer Mode” the notes have a decidedly didactic character. Basic principles of verse speaking that rely on understanding of underlying scansion are always taught separately from the texts to which they apply, so performance students are faced with significant hurdles learning how to identify and execute elisions, contractions, expansions and accentuation issues. (Literary scansion seems almost obsessed with identifying possible spondaic and pyrrhic feet in blank verse lines, neither of which exist in pure form in English verse, at the expense of explaining how regularly occurring challenges like the “missing v rule” or the “the+vowel rule” apply and how these lines are to be spoken.)

*******************************************************************************

Endnotes for "Editorial Principles"

*I am avoiding the use of the term “performance edition,” to describe this project since that term has already been coöpted to describe other, quite different, concepts. Most “performance editions” now on the market, like The Oxford Shakespeare, for example, are standard literary editions that simply take much more seriously the possibility that changes made to the text in rehearsal and performance by the Lord Chamberlain’s Men were either made or approved by Shakespeare and are, therefore, authorial. A second category of “performance editions,” like the recent Arden 3 MND—which says that both the introduction and commentary are designed to present [to readers] the plays as texts for performance—contain performance histories, which annotate known or conjectured performance choices as a way of illustrating the play, but still have identifiably literary aims in doing so. Finally, at least one major edition, The Bedford Shakespeare, suggests that its aim, using a lot of illustrations of performance history, is to help readers imagine a performance. While all of these are valid aims, and while there is room for many different kinds of editions, these aims are not what this edition is designed to do. From my perspective they are mislabeled in that they are not editions intended for creating performances but there is no going back now as these uses of “performance edition” have become common.

†Of course, it is not a new concept to publish a Shakespeare play in the form of a script instead of a literary text, but these versions have not been critical editions, and quite often are not even particularly scholarly ones. In the converse of the “performance editions” described in the previous notes, they are practical adaptations (or often just annotations) designed to lead to a specific production or records of dramaturgical choices that did lead to a specific production. For example, Michael Pennington’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream: A User’s Guide is a fascinating and deeply illuminating book, but it is a specific reading of the literary manuscript, not a critical edition. The recent Arden Performance Editions might, at first, seem an exception, but in the case of MND, they do not reëdit the text at all, but simply use the literary text established by Harold Brooks for the Arden 2nd Series and newly annotate it.

‡These include historical determinants, including the fact that for nearly three hundred years MND was exclusively performed in spectacular musical adaptations that bore only a distant relationship to the printed play, so it was literally true that the audience for print editions was strictly readers; but they also include simple contemporary commercial concerns, like the fact that almost all students in secondary and higher education study Shakespeare as literature at some point, compared to a much smaller number of students who perform the plays.

§Tanselle argues, and I accept, that his proposition for displacing copy-text editing is not a rejection, but rather the logical extension of W.W. Greg’s core arguments in “The Rationale of the Copy-Text” about editorial procedure. Tanselle’s point is that Greg does not carry to completion his own arguments for moving away from the long-standing “best text” approach in favor of empowering editorial judgment, establishing instead a half measure that he had, possibly without realizing it, already substantially undercut.

**Tanselle has said he meant by this that the editor “should not be thinking in terms of altering a particular existing text but of building up a new text, word by word and punctuation mark by punctuation mark, evaluating all available evidence at each step (Millennium, p. 71). Such evidence still includes such standard notions as the genetic lineage of early witnesses, and possibly underlying copy, but the editor is called upon to evaluate it, rather than mechanically accept the “tyranny of the copy-text.”

††Just a few of these generally anachronistic assumptions are that there was a “finished” text, that it was composed in one creative act or revised, if ever, only once (as opposed to continuously reworked over a long period of production), and that the author’s intent was that it should have a “fixed” form rather than retaining flexibility for execution under a variety of circumstances.

‡‡A Midsummer Night’s Dream is a very poor fit for Erne’s theories in any case (as he acknowledges himself in Shakespeare as a Literary Dramatist, noting that in several distinct ways MND is an exception to his general thesis) but it is not his provocative arguments that are being doubted here. It is the simple proposition that even in some counter-factual Gregian universe where there were only two kinds of manuscripts, the authorial draft would be the less theatrical one.

§§Sukanta Chaudhuri, editor of the most recent major new critical edition, for the Arden 3rd Series, retreats somewhat from the rhetoric of certainty other recent editors have evidenced. The result, however, is that he tries to have it both ways—using more qualifying language and noting weaknesses in all individual stands of the long-standing argument, before (rather unconvincingly) concluding that they still collectively add up, and again accepting the overall inference.

***The claim that Holland summarizes relies on an extremely tentative, and problematically circular, argument that the so-called “Hand D” addition to the manuscript of Sir Thomas More is in Shakespeare’s handwriting because it contains distinctive spellings found in print editions of his plays. But then adherents attribute to Shakespeare—rather than compositors, scribes, or copyists—the distinctive spellings in the printed plays because they are found in “Hand D.”

†††Chaudhuri makes this argument in the Arden 3rd edition, but his assertion that, “Most instances would be altered by scribes and compositors. Hence a few cases, or even one, can carry weight,” is not only not supported by evidence, but does not justify the conclusion he draws from it.

‡‡‡This is not to deny that Q1 is the most reliable witness we have. The objections of this editor are a matter of degree, not kind. Where previous editors have thought it something like a first-hand witness to recent events, I think it more like a reporter of hearsay recalled after the passage of several years. Believing that it is the best evidence available is not the same as asserting that it is especially good evidence.

§§§ If F1 had printed an unmodified, rather than this slightly modified, version of Qq, that there is even an editorial consideration here would now be completely invisible.

****While not a perfect analogy, since it was written, then revised, by many hands, I am thinking about the manuscript of The Book of Sir Thomas More as an example of a text composed with smaller slips of paper pasted into larger folios, and having units of dialogue composed without speech headings.

†††† As with most editing questions, G. Thomas Tanselle offers insightful and cogent explanations about the relationship between texts, versions and works. For a more specific discussion of the application of this argument to Shakespeare, see W.B. Worthen’s Shakespeare Performance Studies.