Four Production Cruces

Traditional editions often dwell on textual cruces. (Academic readers will undoubtedly notice the intentional echoing of Harold Brooks' title, "Four Textual Cruces.") A crux is, according to Merriam-Webster, "an essential point requiring resolution." Textual questions do require resolution for performance. Editors sometimes dodge this issue by noting that there are two or more equally valid readings, or that no satisfactory explanation is available. Neither of these is useful for a theatrical performance that must place one, and only one, choice on the stage. Still, Midsummer is a good text with few problems. Brooks' title is a bit of a cheat since he notes that there are actually three more problematic areas in the text, but seven textual issues is a small number.

While these require resolution, they should not blind us to the much larger, looming performance issues, which every production must solve. Here is a brief overview of these issues with a short discussion of the range of possible solutions explored by previous productions.

What constitutes the dream? Whose dream is it?

The title of the play is provocative. The obvious question is: If the play is a dream, whose dream is it? Most literary critics avoid the question by citing Puck's final speech alleging that it is "our," i.e. the audience's, dream. That is not what Puck says, however. He says that if we have found the production offensive then we might imagine that it has all been a bad dream and therefore forgive it. That is not the same thing at all.

Serious productions prioritize the question of whose dream this might be. Corollary questions might be, "Is the whole play a dream, or are some parts dreamt and some parts experienced rationally?"; and "Is the dream important, or is it trivial and insubstantial?" The text, itself, raises these questions—particularly the latter. Theseus and Hippolyta have a dialogue at the beginning of Act V, in which he dismisses the lovers' curious experience in the woods, but Hippolyta counters that their collective experience "grows to something of great constancy." Both in Midsummer and many other places in the canon, dreams are challenged as unimportant. Romeo has this famous exchange with Mercutio, for example:

ROMEO

- I dreamed a dream tonight.

MERCUTIO

- And so did I.

ROMEO

- Well, what was yours?

MERCUTIO

- That dreamers often lie.

A few lines later, Mercutio says:

MERCUTIO

- True, I talk of dreams,

- Which are the children of an idle brain,

- Begot of nothing but vain fantasy,

- Which is as thin of substance as the air.

Although many Shakespearean characters reject dreams as meaningless, the playwright also frequently foreshadows events with dreams of divination that later come true.

Peter Holland says that the only actual dream in the play is the one from which Hermia wakes in Unit 17 (II.ii), in which she images she is being attacked by a serpent. All other portions of the play, he asserts, are not dreams but supernatural experiences that actually happen. While insightful, this does not substantially answer the performance question. It merely shifts the semantics of the discussion from distinguishing between the dream portions of the play and the rational ones, to distinguishing the supernatural portions of the play from ordinary reality.

Twentieth and twenty-first century productions have found a wide range of answers to these questions. The play is frequently interpreted as Bottom's dream or experience, but it has been notably performed as Theseus' (Daniels, 1981) and Hippolyta's dream (Alexander, 1986) as well. Adrian Noble's 1996 film based on his 1994 theatrical production, seemed to imply that it was a child's (the changeling's?) dream.

Peter Brook's production of 1970 changed not only the reputation and critical reading of Midsummer, but arguably reinvented Shakespearean production in our time. He related the supernatural figures to modern psychology as the unconscious reflections of their conscious counterparts. In that sense, his production suggested the play is the collective dream of all of the human characters.

How should the supernatural characters be conceptualized and portrayed?

To the great amusement of actors, few literary questions about the play have received as much attention, and fierce disagreement, as the size of the fairies—with partisans citing lines about fairies hiding in acorns to noting that Tytania interacts with a full-sized Bottom. This issue is largely irrelevant on the stage where regularly-sized humans will portray them. Much more pressing is the question of what the fairies are, and how to capture that on the stage.

Because fairies don't exist outside the imagination, there can be no naturalistic explanation. There is no objective correlative. The fairies must be conceptualized. What do they represent?

We don't know how they were performed in Shakespeare's own time, but given the all-male company and the probable necessity of extensive doubling by the adult males in the cast, the likelihood was that they were understood as rustic, folkloric figures—more like goblins and gremlins rather than what we now think the word "fairy" implies.

After the Restoration, for almost all of the next three hundred years, the fairies were relentlessly portrayed as sentimental balletic figures for the purposes of pageantry. They were included to provide spectacle. All, except Oberon and Tytania, were usually played by children, including Puck.

Peter Brook broke from this cloying tradition once and for all by imagining Oberon and Tytania as Theseus and Hippolyta's dream doppelgangers. Their magical abilities were conceived as "superhuman" skills, which were represented on stage by circus and acrobatic equivalents.

Peter Brook's "Circus" Midsummer

Fair use of publicity materials originally released by the producing company

Since Brook, the fairies have been cast as figures of Elizabethan folklore,

John Light as Oberon and Matthew Tennyson as Puck, at the Globe. Directed by Dominic Dromgoole.

Fair use of publicity materials originally released by the producing company

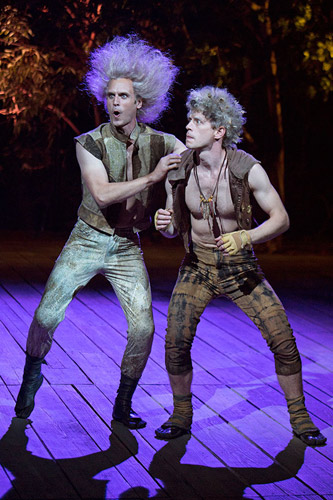

as menacing leather punks,

Old Globe Theatre, San Diego, California

Fair use of publicity materials originally released by the producing company

as giant puppets,

David Ricardo-Pearce as Oberon and Saskia Portway as Tytania, Photo: Simon Annand

Fair use of publicity materials originally released by the producing company

as exotic deities,

Daniel Breaker/Puck Mark H. Dold/Oberon

Fair use of publicity materials originally released by the producing company

as erotic dream doubles,

Elijah Alexander/Oberon and Kymberly Mellen/Tytania at the Utah Shakespeare Festival

Fair use of publicity materials originally released by the producing company

and as comic superheroes.

Jonathan Broadbent/Oberon Lyric-Hammersmith, London

Fair use of publicity materials originally released by the producing company

What is clear is that a wide range of possibilities exists, but strong, clear choices play better than vaguely romantic "Tinkerbells."

The fairies are clearly divided into followers of Oberon and those of Tytania. Both monarchs are described as having "a train" in their initial encounter. These retinues are often gendered, following the gender of their leader, but occasionally reversed. These followers are generally portrayed as siding with their respective leaders as they spar, but have also been successfully portrayed as involuntarily separated pairs yearning for their leaders' reconciliation so that they might be reunited with their lover in the opposite train.

...and of what does their magic consist?

In the same way that the fairies must be conceptualized, so must their magic be. It is possible, even common, to simply treat it as a plot expedient without any further explanation, but in performance the least interesting answer is that the magic is simply magic. Such an answer conveniently solves problems in the world of the play: things happen because they are magically induced. Since magic does not exist in our actual world, however, such answers mean the play doesn’t have much of interest to say about us or to us.

Some such answers are unsatisfying inside the play, as well. Does Demetrius return to Helena at the end of the play only because he remains under a spell? Is Tytania reconciled with Oberon only because he has magical powers that can cause her further humiliation if she does not agree to return to him? These and many other aspects of magic in the play not only lose interest, but ultimately detract from its meaning, if they are just convenient plot devices on the level of a cheaply contrived deus ex machina. If we are to understand that Bottom really did turn into a man-beast but learned nothing from it (or was later enchanted to completely forget it) both his time and ours were wasted.

Much more interesting performances result when the magic is treated theatrically, or psychologically, instead of accepting it at face value. Oberon becomes performatively interesting by casually asserting his invisibility in direct aside to the audience, rather than exiting or somehow being made less visible. (Or as a lighting designer once put it, “This is not the moment to turn off his followspot, it is the moment to make it twice as bright.)

The subsequent scene (Unit 10) is much funnier if Oberon actively intervenes in it, and the actors playing Helena and Demetrius must theatrically “not see” him, than if he simply stands aside and watches it.

Similarly, it is easy for the actors to simply lie “sleeping” on the ground as Oberon and Puck enchant their eyes, but it is theatrically far more compelling when they respond physically. Most modern productions, in fact, have them shift dramatically, sometimes rising all the way to their feet as if sleep walking, before lying back down again. It is the very fact that these actions are obviously illusions being created by actors (of which their underlying characters are “unaware”) as opposed to abstract fictions to be accepted without question, that creates the theatrical pleasure. Suspending our disbelief is half the fun.

Oberon enchants Tytania in a Pennsylvania Shakespeare Festival production

Fair use of publicity materials originally released by the producing company

This question is pushed to its fullest when considering what it means for the characters in the play to be magically induced to “fall in love.” The teenagers in the play, after all, pair into couples, split up, recombine, and reconcile in ways that look only slightly exaggerated in comparison to real life adolescent behavior. (I can anecdotally attest that more than one school cast of the play has had off-stage romantic complications that were at least as byzantine as the onstage ones with no discernable magic involved.) Productions can make it clear to us that more is going on than just “magic flower juice” in a variety of ways, but almost any explanation—in the actors’ minds or the physical staging of the play—is more interesting than a mechanical execution of the stage directions that takes the existence of magic for granted.

The play treats the complications of love and lust seriously, and as essential components of the human condition. A good performance must do more than treat them as after-effects of magical interventions.

How should the changeling be represented?

The central conflict of Midsummer is a fundamentally unexplained quarrel between Oberon and Tytania over the possession of a changeling child. When reading the play this is no more insubstantial than any other element of the plot, but on the stage it can be frustratingly abstract if the changeling has no physical presence comparable to the speaking characters. Nothing in the script compels his appearance, since he is not directly referenced as present in the scene introducing the conflict, and its final resolution happens offstage. Without placing him on stage in some form, however, the plot often loses coherence to a contemporary audience more attuned to visual rather than verbal representation.

In folklore, changelings were misshapen fairy children substituted in the birth crib for beautiful human children, a proto-explanation for birth defects and developmental difficulties. Stories about these exchanged children abound in early modern literature, focusing on the fairy children wreaking havoc on the human world. A Midsummer Night's Dream is the only case in which we see the human child adopted into the fairy world. Shakespeare also seems to have invented a benevolent reason for the exchange rather than attributing it to supernatural malice.

Because the folk sources emphasize the exchange at birth, the changeling is often represented in production as a baby in swaddling. This is the simplest production solution, since it does not require a real child, but introduces the dubious implication that Oberon wants to undertake infant care.

The still accessible 1982 production from the New York Shakespeare Festival in Central Park (recorded for the A&E network) starring William Hurt as Oberon, memorably introduced child actor Emmanuel Lewis as a toddler changeling. The premise that Oberon might be willing to undertake raising the child, now out of diapers, seems more plausible but still raises questions about the nature of the conflict.

Liviu Ciulei's 1985 production for the Guthrie Theatre featured an adolescent changeling, who had grown enough to be an object of affection for Tytania. This made explicit the reason for Oberon's jealousy. Nothing in the play suggests how long ago the exchange Tytania describes took place, so it is possible for the boy to be older now. It certainly makes more sense of the idea that Oberon wants him for a "knight of his train." In this case the boy was also somewhat feminized but reappeared at the end of the evening at Oberon's side in a smaller duplicate of his armor, suggesting the conflict was about Oberon's will that (for good or ill) he be incorporated into the masculine sphere now that he was "of age."

The Gender Politics of the Play

All of Shakespeare's plays assume the gender norms of his time, even if they also question them in the voice of some characters. The inciting conflict of this play is built around a most extreme version of patriarchy, namely that Egeus "owns" his daughter completely, and may therefore select her husband or demand her execution. It is an extraordinarily rare contemporary production that does not interrogate the male privilege of Shakespeare's period. They usually do so emphasizing aspects of the play that challenge, or can be used to rethink, patriarchy.

Hermia's situation is often associated with that of Hippolyta, who enjoys higher status and possibly more freedom. In mythology Hippolyta was the captured queen of the independent Amazons, a band of female warriors that disempowered or eliminated their sons. Her marriage to Theseus was involuntary. Shakespeare refers to this situation at the play's outset but gives only slight indications that it has not resolved into a love match before the play's beginning.

Those "slight indications," however, are generally emphasized in modern production. Although at the beginning of the play Theseus says he cannot override the patriarchal rights enshrined in law, he eventually does just that. The inception of his journey toward doing so is often related to Hippolyta's apparent anger and frustration at the lack of justice shown in Hermia's trial. Because she has no lines to express that dissatisfaction, it is portrayed through behavior.

Hippolyta can be conceptualized as everything from a literal prisoner in a cage (John Hancock, 1966, San Francisco Actors' Workshop) to an early modern noblewoman resembling Queen Elizabeth. (Peter Hall, 2010, Rose Theatre, Kingston) Her reactions in the first scene may range from the growling of a caged animal, to restrained glowering, to faintness brought on by shock, depending on how her character is portrayed and how the circumstances that begin the play are imagined.

The frequent doubling of Oberon and Theseus can make explicit the idea that Oberon's encounters with Tytania constitute a kind of continuity with Theseus' experience and lead ultimately to Theseus' undoing of the patriarchal stifling of Hermia's love. In productions that do not use doubling, the same implication may be made in other ways.

The doubling of Tytania with Hippolyta also intensifies the challenge to patriarchal assumptions of the play. In the dream world males seem far less privileged in the first place. Tytania is obviously equal to Oberon in power, as he must trick her to get his way rather than issue an order or overpower her. In the many source stories of fairy queens, she is always portrayed as more powerful than her consort, if a counterpart to Oberon exists in them at all. She is thoroughly identified with the triple moon goddess Phoebe/Diana/Proserpina—sometimes as another identity—but Oberon is never directly associated with the Sun God, Phoebus Apollo. Although he does not make this explicit in the play, Shakespeare probably shared the assumption that rulers of the supernatural world were goddesses, and the fairy queen was a part of that godhead.

While the script does not overturn male dominance at its end—a situation not helped by the fact that Hermia and Helena do not speak during the final act of the play— productions sometimes do so. Hippolyta's viewpoint is treated as civilizing Theseus. She is often portrayed as prompting his kindnesses to the well-intentioned but bumbling players, for example. Unlike the opening scene, Theseus often makes elaborate shows of deference to her and her wishes at the play's end.

Tytania's participation in the final blessing of the marriage is also strengthened in many productions. Oberon is often treated as a narrator, while Tytania is seen performing the rites that constitute the blessing. Occasionally, some of his lines are simply reassigned to her to make the ending more equal.