List of Characters

In the Court of Athens

-

THESEUS, variable: thee -see-

uhs [ˈθi si əs], or thees yuhs [ˈθis

yəs] Duke of Athens

212 lines (188 verse, 24 prose) distributed across 48 speeches, 1799 total words, or about 10% of the play

The Archibald Fountain, Sidney

Theseus was a classical hero who conquered the Amazons, captured Hippolyta, and then married her. It was he who slew the minotaur. He casually mentions in the play that he is related to Hercules.

-

HIPPOLYTA, hi- pol -i-tuh [hɪ ˈpɒl ɪ ˌtə], Queen of the Amazons, engaged to Theseus

29 lines (22 verse, 7 prose) distributed across 14 speeches, 265 total words, or about 2% of the play

Hippolyta was, in classical mythology, the queen of a band of warrior women known as the Amazons. In the first line of the play, her name alone would be enough of a hint for Shakespeare's audience to know that the setting is ancient Greece, which as the birthplace of philosophy would have associations with order and rationality.

The Wounded Amazon, copy after Phidias

-

EGEUS, ehd- jee -us [ɛdˈʒi ʌs], a nobleman and father to Hermia

41 lines (all verse) distributed across 7 speeches, 302 total words, or about 3% of the play

Egeus' name is an immediate clue to his function as the comedy's "blocking figure," an older man preventing the love match of two young people. His name has associations with fathers in classical antiquity. In fact, in its Greek spelling (Aegeus) it is the name of Theseus' father.

HERMIA, variable: hurm -ee- uh [ˈhɜrm i ʌ] or hurm -yuh [ˈhɜrm yʌ], in love with Lysander

165 lines (all verse) distributed across 48 speeches, 1332 total words, or about 8% of the play

In keeping with the classical setting, Shakespeare chooses names for his four young lovers that come from classical sources but seems to use them to create ironic expectations. Hermia could be intended as a feminine form of Hermes, the name of the god of speed and trickery, but Shakespeare's original audience would be more likely to associate the name with the woman who infamously proved to the philosopher, Aristotle, an obsessive distraction from his studies. In this play, of course, Hermia is the obsession of not one, but two men.

LYSANDER, ly- san -der [laɪˈsæn dər], in love with Hermia

176 lines (170 verse, 6 prose) distributed across 50 speeches, 1449 total words, or about 8% of the play

Lysander is a diminutive form of Alexander, which as a classical name immediately invokes Alexander the Great, probably as humorous overstatement.

Alexander the Great

DEMETRIUS, variable: dih - mee -tree- uhs [dɪˈmi tri əs] or dih - mee -tr uhs [dɪˈmi trəs], Egeus' choice of husband for Hermia

128 lines (115 verse, 13 prose) distributed across 48 speeches, 1110 total words, or about 6% of the play

Demetrius is a male form of Demeter, the name of the goddess of marriage. As applied here, it may imply that he is more interested in the advantageous marriage than the actual woman being proposed as his wife. In Titus Andronicus, Shakespeare had already used this name for a villainous character. Expectations of danger may also be suggested here, although exaggerated for comic effect.

Demeter, Goddess of Marriage

HELENA, hel - uh -nuh [ˈhɛ lən ə] (The accent is never on the second syllable) in love with Demetrius

229 lines (all verse) distributed across 36 speeches, 1852 total words, or about 11% of the play

Like the other three young people, the unloved Helena's name would have ironic associations, in her case with Helen of Troy, who was loved by all too many. In The Iliad, she was said to be the cause of the Trojan War when the Trojan prince, Paris, kidnapped her from her husband, the Greek general Menalaus. Her name is sometimes shortened to "Helen" in this play.

Helen in Troy by Jacque-Louis David

PHILOSTRATE, fil -oh-streyt [ˈfɪl oʊˌstreɪt], Master of the Revels at the court of Theseus

24 lines (all verse) distributed across 6 speeches, 189 total words, or about 1% of the play. (In the Folio, Philostrate's lines are reassigned to Egeus.)

Like the names of Theseus and Hippolyta, Philostrate's name appears in "The Knight's Tale" in Chaucer's Canterbury Tales, where Shakespeare may have encountered it. This part is an important one in the Quarto text, on which this edition is based, but was incorporated into Egeus' part in the Folio, leaving Philostrate as a non-speaking extra in that edition.

In the Fairy World

OBERON, oh -buh -ron [ˈoʊ bəˌrɒn], King of the Fairies

225 lines (all verse) distributed across 29 speeches, 1638 total words, or about 10% of the play

This name for the King of the Fairies is drawn from Spenser's Faerie Queene, the great allegorical tale of the British Renaissance.

Costume design by Inigo Jones, 1609

TYTANIA, ty- tey -nee- uh [taɪˈteɪ ni ə], Queen of the Fairies

141 lines (all verse) distributed across 23 speeches, 1106 total words, or about 7% of the play

The name Tytania appears in Ovid, from which Shakespeare undoubtedly drew it, as another moniker for Diana, the moon goddess. In Shakespeare's play she appears to be a separate personage, but follower of Diana, and a powerful supernatural force, if not a goddess herself. There is no authority for the common contemporary spelling or pronunciation of this name.

Tytania with Bottom, by Henry Fuseli

Robin Goodfellow, a PUCK, puhk [pʌk], attendant to Oberon

206 lines (all verse) distributed across 33 speeches, 1401 total words, or about 10% of the play

The character we most commonly call Puck is named Robin Goodfellow. A puck is what, not who, he is. A puck was a kind of common spirit, or goblin, in English folklore.

Robin Goodfellow, woodcut, 1629

PEASEBLOSSOM, peez- blos - uhm [piz ˈblɒs əm], attendant to Tytania

4 lines distributed across 4 speeches, 5 total words, or less than 1% of the play

COBWEB, kob -web, [ˈkɒbˌwɛb], attendant to Tytania

4 lines distributed across 4 speeches, 5 total words, or less than 1% of the play

MOTE, moht [moʊt], (sometimes called Moth), attendant to Tytania

2 lines distributed across 2 speeches, 4 total words, or less than 1% of the play

MUSTARDSEED, muhs -terd-seed [ˈmʌs tərdˌsid], attendant to Tytania

5 lines distributed across 5 speeches, 8 total words, or less than 1% of the play

A Fairy, attendant to Tytania

36 lines (all verse) distributed across 4 speeches, 200 total words, or about 1% of the play

- The four named fairies in the play all have names derived from nature, and all of which suggest something very small and insubstantial. The first fairy that we meet in the play (in Unit 7, with Puck) does not have a specific name. One of the named fairies usually doubles this role in contemporary performance.

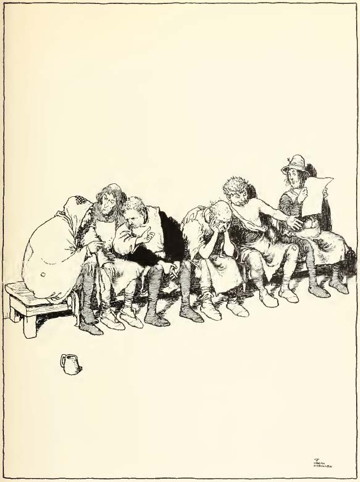

The Artisans of Athens, sometimes called the "Mechanicals"

The "Rude Mechanicals," in an illustration by Heath Robinson, 1919

Peter QUINCE, kwins [kwɪns], a carpenter (Director of Pyramus and Thisbe, who reads the prologue)

74 lines (38 verse, 36 prose) distributed across 40 speeches, 995 total words, or about 5% of the play

Whereas the names of the characters in the court are drawn from classical antiquity, the mechanicals have names that reflect their professions. Quince is reminiscent of "quoins," wedges used by carpenters, but also suggests sharpness.

Nick BOTTOM, bot - uhm [ˈbɒt əm], a weaver (Pyramus)

123 lines (76 verse, 47 prose, 8 song lyrics) distributed across 59 speeches, 2090 total words, or about 12% of the play

Bottom's name derives from the spindle used to wind yarn, but inevitably also brings to mind (given his upcoming transformation) the contemporary usage meaning "ass."

Francis FLUTE, floot [flut], a bellows-mender (Thisbe)

48 lines (34 verse, 9 prose) distributed across 18 speeches, 369 total words, or about 3% of the play

Flute repairs bellows, in which a hole would produce a wheezing or whistling. What is suggested is that he is a teenager whose voice has not yet broken.

Tom SNOUT, [snaʊt], a tinker (Wall)

19 lines (12 verse, 7 prose) distributed across 9 speeches, 166 total words, or about 1% of the play

Snout is a tinker, and his name might reflect the spouts of the tea kettles he makes and repairs, but certainly suggests that he is "nosey."

SNUG, snuhg [snʌg], a joiner (Lion)

11 lines (8 verse, 3 prose) distributed across 4 speeches, 121 total words, or under 1% of the play

Snugness is a desirable quality for the joints, as a joiner is a furniture maker. In this case it may imply "dull" or "rigid."

Robin STARVELING, stahrv -ling [ˈstɑrv lɪŋ], a tailor (Moonshine)

8 lines (5 verse, 3 prose) distributed across 7 speeches, 94 total words, or about 1% of the play

Starveling is a proverbially thin tailor.