Music and Dance in A Midsummer Night’s Dream

The Performing Arts of Elizabethan England.

Both music and dance were important to country life in early modern England. Folk dancing served as the basis for almost all community celebrations, while music making was the most common form of entertainment in daily life. Both art forms were also central to life at court where they served aesthetic purposes; but were also extensively employed symbolically to promote social harmony and signal political allegiance to the crown. Both music and dance were widely understood as metaphors for cosmic and earthly order.

Both art forms were also integral to the early modern theater. Shakespeare’s theatre, especially at the open-air playhouses like the Globe, lacked most means of modern day crowd control such as dimmable lighting and assigned seating. Audiences could be unruly and loud. Pre-show concerts were common to occupy the time of early arrivers. Brass fanfares were used to announce the start of performances because they cut through the hubbub in the auditorium, at least temporarily quieting the buzz, and focusing the audience’s attention.

A 1595 sketch of a performance in progress at the Swan, clearly showing a trumpet player in the gallery. (top right)

The De Witt drawing of the Swan Theatre, the only contemporary drawing of a playhouse interior.

Faithful two-dimensional copy of a work in the public domain

Without the extensive illusionistic scenery of the modern theatre, music was also important to scene setting. Trumpet fanfares like those used in the actual royal palaces announced the entrance of noble characters onto the stage, quickly establishing the location when no scenic clues were available to do so. Hunting horns might signal a shift to an outdoor setting because of their association with the aristocracy at their favorite form of play. Instrumental consorts playing background music could establish social gatherings like Capulet’s ball or Timon’s dinner party. It might even subtly imply scenes are set at night and in the dark, when the theatre was, in reality, brilliantly illuminated in the afternoon sun. In a theatrical tradition much more focused on hearing than seeing, music could convey dramatic information as well as entertain.

References to dance are metaphorically invoked throughout the Shakespeare canon to imply harmony and concord, but especially in the comedies, actual dancing is also used to symbolize (as it was at court) the reaching of agreement or the resolution of discord. Is his study, Shakespeare and the Dance, Alan Brissenden notes, “In some plays, Romeo and Juliet, A Midsummer Night’s Dream and The Winter’s Tale among them, dance is essential to the dramatic action…” Character is developed and plot is conveyed through onstage dancing. The story becomes incomprehensible if it is eliminated.

The Use of Song and Dance in the Play

Central to MND are three songs, two of which are also dances. The play also contains an additional two freestanding dances. All of these play a significant role in the story, including the resolution of the major conflict between Oberon and Tytania in the supernatural plot.

Beyond these five major music cues, stage directions or dialogue also contain direct reference to incidental music on two occasions and specify a trumpet flourish (a kind of fanfare) or the sounding of horns on five more occasions. Performance practice of the time would suggest several more instances, like the beginning of the play for example, where music was probably used but it is not specified in the stage directions of the quartos or the folio.

An instrumental consort of the type that might supply incidental music for a play

Johann Theodor de Bry, detail from Society Couples Dancing

Faithful two-dimensional copy of a work in the public domain

None of the original music has survived. (It is possible, even probable, that pre-existing popular tunes were utilized as settings so there was no “original music.”) It is easy, however, to determine the function and tone of all the music from the words and stage directions alone. For those with historical interest in what an Elizabethan performance might have sounded like several sources have suggested possible settings from extant tunes, ballads, or airs of the time with similar themes and/or meters. A few of these will be discussed below.

This edition identifies 25 probable music cues, and occasions for four dances. In Performance Mode these are marked with this symbol: ♫ Clicking on the symbol will open a note that explains briefly the nature and function of the cue. A longer discussion of all these items appears in the essay below:

The Five Essential Music/Dance Moments

“You spotted snakes with double tongue”

Identified in dialogue as song (and dance) Unit 12, Line 9

FAIRY

- You spotted snakes with double tongue,

- Thorny hedgehogs be not seen.

- Newts and blindworms,

- Come not near our Fairy Queen.

[Chorus]

- Philomel, with melody

- Sing in our sweet lullaby.

- Lulla, lulla, lullaby,

- Lulla, lulla, lullaby.

- Never harm, nor spell nor charm

- Come our lovely lady nigh.

- So good night, with lullaby.

FAIRY

- Weaving spiders come not here.

- Hence, you long-legg'd spinners, hence.

- Beetles black, approach not near.

- Worm nor snail, do no offence.

[Chorus repeats]

Tytania falls asleep.

FAIRY

- Hence, away: Now all is well.

- One aloof stand sentinel.

Of greatest importance are the three songs in the play. The first of these happens in Unit 12, when Tytania commands her followers to perform a roundel (a kind of round dance) and a song. The song has two stanzas in the form of quatrains and a seven-phrase refrain that follows both. A two-line coda ordering all the fairies to disperse—except a sentinel to keep watch—was originally printed as part of the lyrics and it is sometimes sung, but is now usually treated as dialogue.

The refrain of the song is a lullaby that induces the fairy queen to sleep, but the quatrains serve a different purpose. They are incantations against the invasion of serpents and spiders. The function of the accompanying dance in a circle around Tytania is the weaving of a spell that creates a protective perimeter around her.

The structure and tone of the song suggests that it is an art song rather than a folk song, which in turn implies that it was accompanied by an instrumental ensemble. (A stage direction specifically calls for such an ensemble at a later point in the play, and since it was available it is hard to imagine that it was not used here as well.)

The early editions are somewhat confusing about the exact assignments of the singers, but most settings of the song assign the two stanzas to soloists and the refrain to the ensemble. Nothing suggests that specific named fairies must be assigned to any particular lyric, however, so there is great flexibility in how the lullaby might be performed. In practice, it is common for all the fairies to sing the entire piece in unison. It is also fairly common for the stanzas to be spoken or chanted in the manner of an incantation over a musical underscoring with only the refrain completely sung.

In his study of Shakespeare’s music, John H. Long sets the lyrics to a lullaby found in Anthony Holborne’s 1597 collection Pavans, galliards, and other short aeirs. Andrew Charlton adapts an anonymous 16th century piece called “Barafostus’ Dream” for the same purpose. (See bibliography for how to find these realizations.) At this writing a recorded version from Duffin’s Shakespeare’s Songbook, Vol. 1 is available at "You Spotted Snakes"

********************************************************************

“The Woosel Cock” (or “The Ousel Cock” in modern spelling)

Identified in dialogue as song, Unit 19, line 60

BOTTOM

- The ousel cock, so black of hue,

- With orange-tawny bill,

- The throstle with his note so true,

- The wren with little quill—

TYTANIA

- What angel wakes me from my flowery bed?

BOTTOM

- The finch, the sparrow, and the lark,

- The plainsong cuckoo gray,

- Whose note full many a man doth mark

- And dares not answer “nay”—

- …for, indeed, who would set his wit to so foolish a bird?

- Who would give the bird the lie 'though he cry “cuckoo” never so?

In Unit 19, Bottom sings two fragments from what was apparently a popular folksong of the period, although the original tune is no longer known. We do not hear the entire song because Tytania interrupts his singing. The song is not accompanied and is not necessarily intended to be performed well. The comedy of the scene, in fact, comes from the contrast between what we hear from the braying of the transformed Bottom and what the enchanted Tytania perceives as an “angelic” voice.

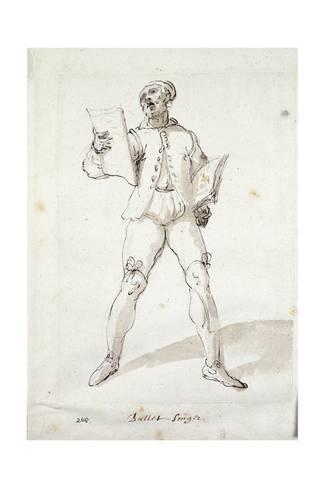

Inigo Jones' rendering of a ballad singer

Faithful two-dimensional copy of a work in the public domain

The lyrics in the printed text includes two quatrains, followed by two sentences that are usually interpreted as spoken dialogue, but which Long thinks was a refrain. The ditty is a just a device for Bottom to calm himself, and the lyrics are not particularly important or relevant to the story. (The song is about birds, ending with the cuckoo, references to which figure in many Elizabethan jokes and folksongs for its similarity to “cuckold.”) The lyrics easily fit tunes from a large number of Elizabethan ballads and folksongs, as it is written in a simple meter. It is, in fact, an example of the song meter (as opposed to the sonnet form) of “eight-and-six.”

You can hear a rather light-hearted recorded version of Duffin’s conjectural setting of the song at "The Woosel Cock". Another, much more sincere, version of a different setting is available at "The Woosel Cock"

Because the lyrics are not important to the plot, modern productions sometimes substitute an entirely different piece of music replicating the effect of using of a popular tune familiar to the audience rather than using the now-obscure folksong. The editor directed a production in which, at the suggestion of the student dramaturg, Bottom sang modern-day hipster crooners’ favorite song, “Wonderwall.”

*******************************************************

Music such as charmeth sleep

Identified in dialogue at Unit 33 (IV.i.b), Line 67

The climactic use of music and dance in Midsummer takes place in Unit 33 at line 65, when Tytania commands it, or more likely at line 67, when Oberon repeats the order. Tytania (speaking to unseen forces) asks for “music, such as charmeth sleep.” Oberon then follows up her royal request with “Sound music. Come, my queen, take hands with me/ and rock the ground whereon these sleepers be.” His suggestion is that they dance in a manner that will “rock” the ground in the same manner that a mother would rock a cradle, combining with the music to keep the four lovers (and Bottom) in a deep sleep. Oberon and Tytania then dance together, ending their enmity, and resolving their quarrel over the changeling boy that has disrupted nature.

Long suggests that there are two separate musical episodes here: First, the music that “charmeth sleep” as ordered by Tytania, and once it is completed, a separate piece of music to accompany the dance suggested by Oberon. In modern production only one piece of music is commonly used, but it sometimes begins when Tytania commands it, and then extends when Oberon gets the idea to dance to it as a tool of reconciliation.

We know nothing of the original music, but it was certainly supplied by an off-stage consort, as it is supposed to be magically induced. It perhaps represents the harmonious “music of the spheres” being made audible. The purpose of this music is to refresh and restore the lost senses of the mortals after their mentally and physically trying night in the woods. We have every reason, then, to think that the music might be calm and peaceful. Long proposes John Dowland’s “Sleep, Wayward Thoughts” as found in his First Book of Airs (1597) as a good equivalent for what might have been played at this point in the original production. Numerous recordings of this piece can be easily found, such as at "Sleep, Wayward Thoughts"

Johann Theodor de Bry, detail from Society Couples Dancing

Faithful two-dimensional copy of a work in the public domain

The dance which Oberon and Tytania then perform to mark the restoration of their relationship was probably a pavane, a stately court dance of the period. A simple demonstration of this dance can be found at "Pavane"

*******************************************************

Bergomask

Dance identified in dialogue, occurring at Unit 49 (V.i.m), line 309

In the early modern period, theatrical events involved more than just the formal play. They might include pre-show crowd pleasers like fencing bouts or short concerts, and almost always ended with some kind of postlude and a dancing demonstration. In keeping with theatrical custom, after performing Pyramus and Thisbe, Bottom and his crew offer just such an epilogue or a dance. Already familiar with their ability to deliver verse, Theseus wisely chooses the latter.

The dance they propose to perform is a Bergomask, a lively dance that originally poked fun at the rustic and unsophisticated folk dances of the Bergamo region of Italy. It was perceived then something like tap or clog dancing is now received— that is, as something less elevated than art dance like ballet, but also as possibly more entertaining and popular.

Bottom’s proposal to the Duke is that two company members will perform this dance, but even if only two start it off the Bergomask is almost universally performed by the whole group of mechanicals in modern production. As opposed to the ethereal dancing of the fairies that has preceded, and will follow, this dance, the Bergomask is usually a vigorous, earthy dance. It is not always accompanied by anything but clapping and stomping along to the insistent rhythm, but if music is desired almost any lively folk or popular dance will serve in this location.

Sebald Beham's "Sept. and Oct." from The Peasant's Feast, or the 12 Months

Faithful two-dimensional copy of a work in the public domain

John Dover Wilson suggests that this piece serves as an anti-masque to the masque that will follow (see next entry), so even though it should serve as a grotesque parody, it still might be musically and choreographically related to Oberon’s song.

One of Shakespeare’s castmates, Will Kemp (who might well have been the original Bottom), was a specialist in post-show jigs, and there is an extant tune called “Kemp’s Jig” that gives a sense of what kind of music might be used originally. A recording is available at: "Kemp's Jig"

****************************************************************

“Now until the break of day,” also known as Oberon’s song

Identified in dialogue as song (and dance) Unit 51, Line 348

OBERON

- Now, until the break of day,

- Through this house each fairy stray.

- To the best bride-bed will we,

- Which by us shall blessèd be,

- And the issue there create

- Ever shall be fortunate.

- So shall all the couples three

- Ever true in loving be,

- And the blots of Nature's hand

- Shall not in their issue stand.

- Never mole, harelip, nor scar,

- Nor mark prodigious, such as are

- Despisèd in nativity,

- Shall upon their children be.

- With this field-dew consecrate

- Every fairy take his gait,

- And each several chamber bless,

- Through this palace, with sweet peace.

- And the owner of it blest,

- Ever shall in safety rest.

- Trip away. Make no stay.

- Meet me all by break of day.

Oberon begins the scene by calling on his followers to give the house “glimmering light.” Most modern productions accomplish this by having the fairies enter carrying flickering candles, but since in Elizabethan times the carole was a dance performed with linked hands, he is more probably (supernaturally) causing or inviting twinkling starlight inside the chamber. With modern lighting technology, some productions now use small LED lights sewn into the costumes or mounted on headdresses to provide this effect and free the actors’ hands.

The form of this masque is six lines of (probably spoken) instruction from Oberon, followed by a quatrain extending these instructions by Tytania. At that point, the Folio text has a heading that says simply, “The Song.” It is followed by eleven couplets which are not specifically assigned to any singer, although the quartos omit the heading and assign all of them to Oberon. (Samuel Johnson thought that this heading indicated that a (lost) song was inserted here, and that the couplets were a spoken section to follow it. The New Oxford Shakespeare seems to accept this interpretation. While it is common for song locations to be indicated in this way in the Folio, without printing their words, the fact that the couplets were set in italic type strongly suggest that Dr. Johnson was mistaken, and that they are lyrics.)

Modern settings utilize a wide variety of assignments of singers to these lyrics. While Oberon sometimes sings or intones the whole song, just as often he shares it with Tytania and/or with the full ensemble. The couplet “To the best bride-bed will we / Which by us will blessed be” seems to indicate plural singers, so it is more than defensible to think that all or part of the song should be harmonized (as were most caroles) by all the participants.

Ancient caroles, which had something of a processional quality, were generally not accompanied but the use of an instrumental consort elsewhere in the play makes it plausible that one was also used here.

Andrew Charlton adapts the anonymous 16th century piece, “I Loathe that I Did Love” as a setting that gives some sense of what the original might have sounded like. (Long prints “The Urchin’s Dance,” written by Edmund Pierce for Thomas Middleton’s Blurt, Master Constable as a suggestive analogy, but the tune does not fit the meter or form of Oberon’s song, so it serves only to give a feeling of tone and style.) Few modern settings attempt to use an Elizabethan style, but most have a reverent and harmonious style that provide a fitting conclusion to the play.

Other Music

Flourishes and Fanfares

In addition to the essential music cues above, the play calls for short fanfares or flourishes, lasting up to ten seconds, to start scenes where Theseus is entering in his official role and twice to announce sections of the play-within-the-play, Pyramus and Thisbe. Theatrical practice might suggest use of these on some other occasions, as well. In the comprehensive list of musical cues (below) there are notations about both specified and implied use of trumpets and horns in the play. All of these are also notated in Performance Mode. These are among the 25 cues mentioned at the start of this essay.

Of particular note, however, is the instance of “Sound horns” after Unit 34, line 120. Because supernatural music has been used to lull the lovers and Bottom into a deep sleep, this use of mortal music to wake them and return them to their full sensibilities serves as a kind of book-end. Some effort might be expended to relate this flourish to the music that “charmeth sleep” in some manner.

Optional incidental music

Because Midsummer is such a musical play, it often involves commissioning a complete musical score. For a production utilizing such a score, it is sometimes useful to request a few minor pieces of music beyond those specifically called for by the text.

In addition to the music noted above, it is common for the mechanicals to have an identifying theme that is played at the beginning of their scenes to set the comic tone, and the fairies often have their own identifying theme, as well. Notes for optional occasions where such music might be used appear in the list of cues below, and in Performance Mode.

Bottom calls for music performed on the “tongs and the bones” in Unit 32. These are instruments something like the triangle and castanets. Tytania has a line right after which seems like a distraction, and the quartos have no musical cue here, but the Folio specifies that these instruments actually play. This is an optional occasion for a short, perhaps interrupted, piece of music.

Finally, the transition between Units 33 and 34 may require a short musical interlude of some sort if Oberon/Theseus and Tytania/Hippolyta are doubling to cover their costume change and re-entrance.

One possible incidental dance

In the middle of Unit 18, after Bottom is transformed into an ass, there is an often overlooked possible dance cue. As his friends scatter in amazement, Puck enters (invisible to them) and says, “I’ll lead you about a round.” Although he may be speaking metaphorically, the literal meaning of this line is that he will lead, or “call,” a round dance. (In America, these are idiomatically called “square” dances.) One comic way of handling this scene is to turn it into a supernaturally compelled dance, and it may need both incidental music and choreography.

Comprehensive List of Cues (Indented cues are optional)

Pre-show

Specified entrance Flourish at beginning of Unit 1

Possible exit flourish at end of Unit 2

Possible rustic entrance music at beginning of Unit 6

Possible fairy entrance music at beginning of Unit 7

Possible entrance flourish for Oberon and Tytania at beginning of Unit 8

Entrance music/underscoring, blending into fairies’ song-dance at beginning of Unit 12

Possible rustic entrance music at beginning of Unit 18

Possible madcap music for chase in middle of Unit 18 (Duffin cites “Sellenger’s Round,” one of the most popular tunes of the period, as a possibility. Many recordings are easily available.)

Bottom’s song (The Ousel Cock) in Unit 19

Exit music before modern intermissions, end of Unit 19, (III.1)

Intermission

Possible music for Oberon’s entrance to start second half, top of Unit 20 (III.ii.a)

Possible fog/quarrel music for (III.ii.k-m) Units 29-31 (Duffin provides a possible setting using the tune found in an Elizabethan manuscript with very similar lyrics.)

Entrance music for fairies at top of Unit 32 (IV.1.a)

Possible music for “Tongs and Bones” in Unit 32, after line 15 (Folio specifies, Quartos don’t)

Ethereal music in (IV.1.b) Unit 33, when Tytania and Oberon command it. (Lines 65, or more likely 67)

Previous cue continues as a dance

Possible transition music between Units 33 and 34 (IV.1.b and c) possibly blending into specified flourish for entrance of Theseus - see next cue

Flourish for Theseus' entrance at top of Unit 34

“Sound horns” after Unit 34, line 120

Possible exit music for Theseus after Unit 34, line 169

Possible Rustic music for top of Unit 36 (IV.ii.a)

Flourish for Theseus at beginning of Unit 38, which is top of Act V

Flourish before Prologue at Unit 40, after line 111. (Folio only SD)

Flourish before Dumb Show (Unit 42) (Folio only SD)

Bergomask dance at Unit 49, after line 309

Song and dance at Unit 51, after line 347

Curtain Call/Post show

Lyrical passages

Many verse passages in the play are extremely lyrical in nature. Although there is no indication that these were intended as songs, several of these “purple” passages have been set to music often, especially incantations and speeches that are cast in iambic tetrameter, sometimes called “magic meter.” The following list gives a sense of speeches from the play for which it is easy to find musical settings:

“Love looks not with the eyes” (Unit 5)

“Over hill, over dale” (Unit 7) Gooch and Thatcher list 43 settings

“I know a bank where the wild thyme blows” (Unit 11, line 252) – Gooch and Thatcher list 38 settings

“Up and Down.” (Unit 18, line 45)

“Flower of this purple dye” (Unit 23)

“Be as thou are want to be” (Unit 33, line 52)

“Now the hungry lion roars” (Unit 50)

“If we shadows have offended” (Epilogue)

Annotated Musical Resources

Charlton, Andrew. Music in the Plays of Shakespeare: A Practicum. Garland, 1991.

(Charlton’s book is now out of print, but it is well worth tracking down for its thorough cue sheets and printed music for suggested settings for all the major pieces. The discussion of tone and purpose of each piece is very helpful for pre-planning any production whether or not there is any interest in historically accurate recreations.)

Duffin, Ross W. Shakespeare's Songbook. Vol. 1, W W Norton, 2014.

(The most recent work providing a discussion of the music along with printed possible settings for Shakespeare’s songs, this excellent volume is easily available. It has a companion CD carried by Naxos of America, which makes it possible to hear recordings of many of the most important musical pieces. The recorded music has been made available separately by the publisher on many streaming music services, so one can easily listen to most of the examples. The greatest virtue of this book is that it discusses many pieces of incidental music in addition to the major songs and offers suggestions from the period repertoire that might satisfy them. The glaring weakness, at least as concerns Midsummer, is that it inexplicably omits any discussion of the final song, “Now Until the Break of Day.”)

Gooch, Bryan Niel Shirley, et al. A Shakespeare Music Catalogue. Vol. 2, Clarendon Press, 1991.

(This academic catalogue does not provide any music but is simply an exhaustive list of known settings. For Midsummer that totals in the thousands. The discussion of Midsummer is illuminating as it covers incidental music for the theater, settings for songs intended for concert performance, related pieces like Britten’s opera, and settings of verse not originally intended as song. Although it has not been updated since 1991, it is still exceptionally helpful.)

Long, John H. Shakespeare's Use of Music. Da Capo Press, 1977.

(Now available in an inexpensive reprint by Forgotten Books, Long’s discussion of music is sometimes marred by outdated editorial assumptions, but his musical selections are useful and his observations about the uses of the music can be very astute. He offers very different suggestions of Elizabethan pieces that might work from Duffin or Charlton, so this is a good additional resource.)

Place, Gerald, and Rebecca Hickey, singers. Dorothy Linell, Lute. Music for Shakespeare's Theatre. Naxos 8.570708, 2008. Musical Recording.

(This recording of period music for Shakespeare’s plays, also made widely available by the publisher on streaming services, includes “The Woosel Cock” and “You Spotted Snakes,” along with a short version of “Kemp’s Jig.”)